Meet Gary Dean

A Jakarta Expat interview with Gary Dean

Parts of this interview were published in Jakarta Expat, March 2013

Jakarta Expat: So Gary, where do you come from, where did you grow up?

Gary Dean: I was born in Perth, Western Australia in the pre-Sputnik era. I grew up in the northern suburbs of Perth.

JE: How long have you been living in Indonesia and what brought you here in the first place?

GD: I’ve lived in Indonesia continuously since 1996. Why did I come to Indonesia? Firstly and principally, because it was not Australia. Psychologically, Australia was choking me; it is an orderly, over-regulated, self-satisfied country that is in love with its own image. I desperately needed some disorder in my life; and Indonesia delivers this in truckloads! In Indonesia, absolutely nothing can be taken for granted.

JE: So how did you get from studying Animal Husbandry to becoming the director and senior consultant for Okusi Associates?

GD: It may seem incongruent, but in fact I see great logical continuity in my journey to where I am today. But for me, my starting point is not animal husbandry, but rather the trombone.

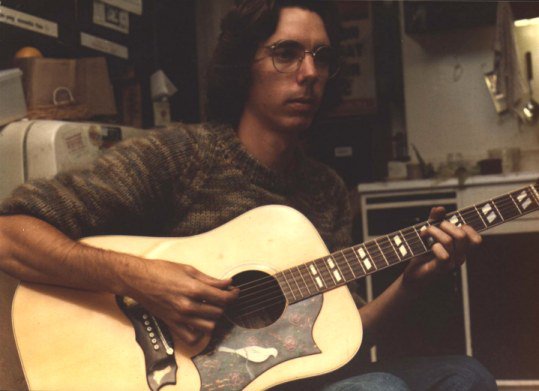

I attended a ‘special’ government high school where music was a major part of the curriculum. For over 3 years, I spent on average 20 hours a week doing instrumental lessons (trombone), concert band rehearsals, and music theory classes, in addition to regular concerts throughout the year.

During this time I also taught myself the guitar. It seemed inevitable, to both myself and all around me, that I was destined to be a musician. But this was the early ’70s, and times were a-changing in Australia. I left school and hit the Australian hippie trail at age 17, joining bands and trading on my music skills to stay alive.

The back-to-the-land movement was strong at that time, with any hippie worth his/her salt heading to the countryside to live in agrarian communes, or at the very least, talking about doing so! This was the beginning of my interest in agriculture, and livestock in particular. I started raising dairy goats, first in Tasmania, then in Fremantle, Western Australia. I formalised my interest by doing a number of college courses, including a Certificate in Animal Technology, Certificate in Animal Nursing, and an Associate Diploma in Agricultural Technology.

This all led to a few agriculture consultancy gigs using my skills and knowledge in this area, including for the Anglican Church, the WA Conservation Council and TAFE.

However, my agricultural career was cut short: I got a job as a computer programmer with a front-company for the Australian Labor Party. This company was set up specifically to undertake polling and campaign activities for the ALP all over Australia, state and federal. My qualifications? Well, apart from being viewed as politically ‘reliable’ in some sense, it seems I was the among the very few at that time (1985) that knew anything about programming the newly-released IBM Personal Computer. I had developed a least-cost ration formulation program for ruminants (goats, sheep, cattle) for a number of small hand-held computers. Thus was I thrust into the world of mainstream political campaigning as a computer systems engineer, devising programs for opinion polling, electorate management and direct mass mail.

But, by 1993, I was quite burnt out. I liked computer programming, but it was never what I intended to do with my life. I needed to change, and I really needed to get out of Australia, which was suffocating me. I thus formalised a plan. I would move to Indonesia. Why? Because it was close, interesting, and potentially not boring.

I started full-time Indonesian language training in 1994, doing an Associate Diploma in Language Studies a Metropolitan College, before transferring to Murdoch University’s Bachelor of Asian Studies program. My first year in this degree course got me to Universitas Gadjah Mada in Yogyakarta under the ACICIS program. And thus started my Indonesian adventure….

In 1997, while still at UGM, I set up a consultancy in Yogyakarta called Okusi Associates (okusiassociates.com) catering to the then-booming furniture industry. I set up companies for foreigners wanting to manufacture and export, as well as assisting with government and community relations.

Actually, 1997 was not a good year to start a business of any sort in Indonesia, if you will permit the understatement. The country was collapsing under the weight of the Asian financial crisis, and the repressive Soeharto regime was teetering. Everything fell into a heap in May 1998, but I had nowhere else to go. Unlike the tens of thousands of sensible foreigners who packed up and left, I stayed.

All the while, I continued my degree studies externally, obtaining my BAsianSt in 2000.

Business was understandably quiet for a few years after the fall of Soeharto. I moved my company to Jakarta in 2000, opening an office in Jalan Kebon Sirih Barat, just off Jalan Jaksa.

By 2003 the consultancy part of my business was starting to get very busy. Foreign investors were entering Indonesia again, albeit slowly. In 2006 I opened a branch office in Bali, and in 2008 in Batam. The Jakarta office moved to Jalan Thamrin in 2011. In 2012, Okusi’s three-storey back-office, Graha Okusi, in Kebon Sirih, was opened.

Today Okusi has 55 employees, and an in-house notary, engaged in company establishment, accountancy and tax reporting, immigration services and research. Okusi has established more PMA companies than any other firm in Indonesia.

So, this is what happens when you take up the trombone. I truly often wonder what would have happened if I had learnt the piano instead.

JE: It seems your business has grown considerably. Could you tell us what you specialize in and what kind of services Okusi provides?

GD: Yes, it has grown, But this didn’t happen by accident, and it didn’t happen overnight.

Okusi’s core business is PMA company establishment. When starting out in Yogyakarta, I quickly figured out that setting up a company in Indonesia was not so much a legal problem, as a sociological one. The strictly legal aspects of setting up a PMA were relatively easy. What was difficult — and what remains difficult — is dealing with predatory government officials to obtain the required permits to operate a business. Essentially, Okusi specialises in dealing with Indonesian government and bureaucracy.

Once a company is established, foreigners nearly always require assistance with work permits and tax compliance. For this reason we added immigration and tax reporting services in 2006.

Okusi has always maintained a full-time research section to undertake surveys and gather information for clients wanting to invest in Indonesia.

In 2010 Okusi’s IT services section (www.okusi.co.id) opened, specialising in Linux and Open Source. As part of this Okusi established and maintains the Ubuntu Indonesian Forum (www.ubuntu-indonesia.com) to promote the use of the Ubuntu variant of Linux. We regularly sponsor seminars and workshops for this Forum.

JE: Indonesia ranks 128th out of 185 in the Ease of doing Business Report 2013, yet Bloomberg is currently encouraging investing in Indonesia’s booming economy. Do you think the Government is transparent and stable enough to invite foreign investors into Indonesia?

GD: The investment boom in Indonesia over the past six or seven years is undeniable. The question is: why? Although Indonesia has come a long way since 1998 in terms of its democratic institutions and investment climate, many parts of the of the old regime have remained stubbornly resistant to reform.

The Autonomous Region laws of 1999 led to a massive expansion of the system of corruption, which had been more of less centralised up until then. Besides the central government and the 33 provincial governments, there are now also over 400 regency (kabupaten) governments, and all of these institutions can (and do) make their own rules, regulations and policies.

Overlaid onto this is a predacious and xenophobic culture within the apparatus of the Indonesian state, with the politicians, bureaucrats, the police and military, assuming that the world owes them something, foreigners in particular.

The Indonesian bureaucracy is an uncoordinated, seething mass of corruption and incompetence, and bureaucrats generally have no sense of duty for the common good of the country, only to their own, narrow and selfish purposes.

Does the average Indonesian bureaucrat care about foreign investment? No, they truly do not give a damn. And in fact, may well view it with suspicion.

Indonesia has done well over the past few years not because of the government, but in spite of the government.

Also, because Indonesia was largely shielded from the world financial meltdown of 2008, thanks partly to the hard medicine administered by the IMF in 1997-98, investors have had little choice. Indonesia has looked good as an investment destination only because the rest of the world was/is so bad. It has had nothing to do with government reform or changes, as absolutely nothing has changed in a true policy sense since 2004. In fact, the situation within the bureaucracy has become much worse over the past few years, with arbitrary, sudden changes in regulations and policies happening continuously across all levels of government.

I could go on and on, of course. I think most of your readers already know this stuff. So if things are so bad here, why do we stay, and why do new investors continue to come to Indonesia?

In spite of the chaos in government, the predatory bureaucracy, and the sense of entitlement by Indonesian elites, Indonesia is a great place to make money. Indonesia is also intrinsically very stable in a social sense.

Unlike in many other developing economies, Indonesia allows 100% foreign ownership in many sectors, including consulting services, import and export trading, manufacturing and many others. Compare this, to say, the Philippines or Thailand, where foreign investors are compelled to take on 51% local ‘partners’ across all sectors.

Indonesia is a great place to live, and Indonesians are great people. Yes, they have their shortcomings here and there, but expats — bule expats in particular — are not exactly paragons of virtue either.

JE: I heard that you are recently married, congratulations! How did you meet your wife and where did you get married?

GD: I met my wife in Yogyakarta on a visit there in 2006. She then joined Okusi in Jakarta. I made an honest woman of her in Jakarta last December, on the last day of the Mayan calendar. As we all now know, the world didn’t come to an end, so now I guess I’m stuck with her. It’s just as well I actually like her. A lot.

JE: Do you plan on moving on from Indonesia, or have you planted permanent roots?

GD: I have lived in Indonesia continuously since 1996. I came here with the mindset of an immigrant rather than an expat. I make occasional trips to other parts of Asia, and made a quick visit to Australia in 1999, but essentially I don’t travel much at all.

I am a few weeks off becoming an Indonesian citizen, so I guess this means I’m here for good. Nearly everything I care about in terms of family, friends, assets and interests, is located here in Indonesia. So, no, I won’t be going anywhere.

Ibu Anita passed away on the 8th of April 2015.