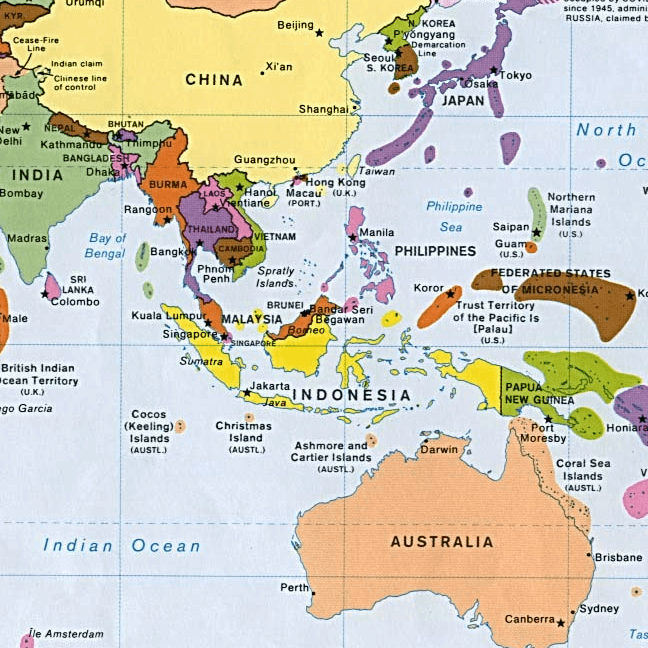

Since the very beginning of a notion called ‘Australia’ some 200 years ago the European occupiers of this continent have rarely felt at peace with its geography. As a transplanted, predominantly European, society situated within Asia,[1] far from the homelands-of-the-heart in Europe, Australians have always felt an acute sense of threat from the north. In nearly every respect, Australia is profoundly differences with the nations of Asia: race, history, culture, social structure, and population size and density, just to name a few. Australia is truly an oddity within its region; it doesn’t really fit. Separated by vast distances from the other rich, English-speaking, mainly-white, ‘Echelon’ nations (Britain, the US and Canada), Australians feel an acute sense of isolation in this region, like a ‘continent adrift’.[2]

It has only been these past few decades that Australia has pursued a relatively independent foreign policy, out from under the shadows of both Britain and the US. Australia’s unique historical circumstances have led to the development of a certain set of attitudes and characteristics that underlie its foreign relation’s behaviour. Among other characteristics there has been a dependency syndrome, first with Britain, and then with the US. An acute sense of geographic isolation from the Anglo-American cultural hearthlands is also evident along with a corresponding sense of threat from Asia. There is also a kind of compensatory behaviour in the manner in which Australia aggressively projects itself the outside world in international forums especially, perhaps fearful of being forgotten.

For all the rhetoric of ‘closer engagement with Asia’ espoused by successive Australian governments over the past few decades, the fact remains that it is the US and the West generally that determine the actual execution of most Australian foreign relations, trade and security policy.[3] For all the treaties with the countries of Southeast Asia, most Australians would know that should Australia call for assistance in time of need, such assistance would not come from within the region, at least not in any active form.

In the light of this, it needs to be asked, is there indeed a place for Australia in Asia? And if there is a place, to what extent can Australia influence Asia, in particular through regional forums? Can Australia ever be accepted as part of the Asian community? The reality is that the answer to most of these questions lies with Asia, and not with Australia. This essay shall start by giving a brief overview of Australia’s cultural history and the way this has affected its ties with the outside world, especially in relation to security, before moving on to describe Australia’s emphasis on multilateralism in its foreign policy, and its attempt to establish a voice within the internal discourses of Asia.

Australia’s early history was dominated by British outlooks and interests, reflecting an immigrant population overwhelmingly of British stock. Australia was a mere home away from home, a far-flung outpost of the Empire. Even for those who had never set foot in Europe, the hearts and minds of most Australians were rooted firmly in the pastoral English countryside up until recent times. In virtually every realm of life - cultural, social, political - Australians looked to London for guidance and support.

Clearly, Asia is profoundly different from Australia, with contrasting disparities in nearly every facet of life. Australia is amongst the richest countries in the world; Asian countries amongst the poorest. Australia is the least densely populated landmass on the planet; Asia the most densely populated. Culturally, Australia is unambiguously oriented towards the West, taking its cues from the US and Britain. Socially, Australia is a transplanted modernist society with little history to speak of, whilst much of Asia remains traditional in many of its outlooks, with histories and civilisations stretching back to antiquity. Politically, Australia is a pluralist liberal-democracy, whereas Asian politics tends towards the patrician or populist. Australia gives a high importance to rule-of-law and binding agreements, whereas Asia places much greater importance on the maintenance of the appearance of social harmony and upon dispute resolution through consensus. Even Australia’s unique fauna and ancient geology is used as a point of differentiation and ‘otherness’ by many Asians.

With these great and fundamental differences in mind, it should be no great surprise that Australia experiences difficulty in establishing discourses with Asia and its component states. Many Asians are thus confused when confronted with the proposition that Australia is a ‘part’ of Asia. Proximity is not a factor in the minds of many Asians when considering what is ‘Asia’ and what is not. If it were, then Russia would surely also be considered part of ‘Asia’. Similarly, West Papua is considered, by some at least, as part of Asia because of its tie to the Indonesian state, but neighbouring PNG is not. Perhaps we are asking the wrong question: it is not a case of ‘where’ is Asia, but rather ‘what’ is Asia. Nevertheless, Australia is clearly not in a position to demarcate the boundaries of ‘Asia’ in either geographical or cultural senses.

The Hawke-Keating period of government (1983-1996) saw the development of a much more multilateralist approach in Australia’s foreign policy, and an activist role for Australian foreign ministers, in particular, Gareth Evans. Great political and economic changes occurred in the international system during this period, in particular, the rise of Japan as a rival to the US in the economic realm, the emergence of Asia as a world economic power, and the demise of the Soviet Union and subsequent ending of the Cold War.[4]

From the mid-80’s the emphasis of Australian foreign policy shifted increasingly to multilateralism and so-called "coalition-building", and collective security within a regional framework.[5] Australia identified itself as a ‘middle power’ capable of acting as an honest broker on the international stage. Australia began to view itself as one of a group of states with liberal-democratic traditions that could act in concert to influence the larger powers, recognising the limits of a ‘middle-power’ state acting alone unilaterally.[6]

It was in the mid-80s that the Hawke Labor Government ‘discovered’ Asia, and set about a deliberate course of ‘engagement’ with this new found region. At this time all parts of Asia were experiencing phenomenal growth rates and increases in disposable income, and for the first time the populations in many of these countries could afford to purchase Australia-made goods.

Asian-cynicism towards this sudden interest by Australia was almost immediately evident, with some taking the reasonable view: "Where was Australia when we were poor?"[7] The fairness or otherwise of these views is debateable, especially when it is recalled that Australia had for many years provided a not inconsiderable amount of aid and security to many countries in Southeast Asia in particular. However the perception remained strong in some Asian countries that Australia was simply trying to jump on the gravy train.[8] The Prime Minister of Malaysia, Dr Mahathir Muhammad, put it acidicly: "When the British were rich, Australia wanted to be British. When the Americans were rich, Australia wanted to be American. Now that Asia is rich, Australia wants to be Asian."[9]

Australia’s motivation for wanting to ‘hook up’ with Asia was not only pushed by Asia’s economic momentum, but also by the very real threat at that time of the world breaking up into economic blocs as a result of serious trade disputes between Japan and the US, and the US and Europe. It seemed that the world was about to be divided between NAFTA, the EU, and some as-yet undefined Asian grouping. Australia was in great danger of being left out. Against this backdrop in 1989, during a period of exceptionally high Australian diplomatic standing in the Asia-Pacific, that then-Prime Minister Bob Hawke proposed what was to become APEC (Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation).[10]

Initially, the APEC proposal was framed so vaguely that it was thought that Hawke was talking about a grouping only incorporating East Asia. With the trade tensions existing at the time, the proposal gained some quick support, especially from a key nation, Japan. Curiously however, membership of the grouping was almost immediately expanded to incorporate the US. In hindsight this was probably the death sentence for the proposed bloc. Naturally, if the US was to join, Canada and Mexico could not be left out, as they formed an existing bloc with the US in the form of NAFTA. Then the US’s poor southern cousins, Chile the first amongst them, demanded "in". The APEC grouping thus rapidly collapsed into incoherency, with the only commonality being that all the nations shared waterfront in the form of the Pacific Ocean. Even Russia, an economic cripple with its centre of power in Europe, demanded admission on the basis of it’s territory that faces into the North West Pacific.

What should have been one of Australia’s finest diplomatic achievements almost immediately turned into a farce, partly because of Australia’s (and also Japan’s) inability to say ‘no’ to the US, something that would not have been missed by many Asian observers.

This lack of coherence gave opportunity to Australia’s political competitor in the region, Malaysia, to put together an alternative proposal in 1990, called the East Asian Economic Caucus (EAEC), re-centring the would-be bloc on East Asia, and specifically and pointedly excluding Australia and New Zealand. Whilst countries such as Japan and Singapore quietly equivocated on Australia’s exclusion, at the end of the day they went along with Malaysia’s conception, possibly as insurance against APEC’s probable failure.[11]

Later, in 1995, the Labor government came close to admitting the failure of APEC by outlining a concept called the ‘East Asian Hemisphere’, incorporating all the countries between longitudes 90’E and 180’E, ie, Australasia and East Asia, specifically excluding countries facing onto the Eastern Pacific.[12] However, by this time it was probably too late to retrieve the situation, with the concept being an obvious attempt to undermine Mahathir’s EAEC with an alternative East Asian vision. Exclusion from EAEC would leave Australia isolated in the international trading environment in the event of APEC’s demise, as now seems likely to occur. EAEC is unambiguously regional, and a more-or-less culturally cohesive grouping of far superior coherence than APEC.[13]

Australia’s continuing attempts to ingratiate itself into the Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM) also indicates that Asia – not just Malaysia’s Mahathir – simply find Australia hard to accept as being ‘Asian’. Notwithstanding the barely audible protests of Singapore and Thailand over Australia’s exclusion, the majority of Asian nations participating in ASEM are conspicuous by their silence on this matter.[14] And from their point of view, this is completely reasonable: Australia – for all its pretence of multicultural diversity – is a predominantly European nation with a completely Western perspective. For Australia to sit on the Asian side of the ASEM dialog is simply absurd. Once again, this clearly demonstrates the cultural delineation of Asian-ness, rather than the geographical and economic delineation much preferred by Australia.

Security issues have always dominated Australian foreign policy. The current ‘ring of fire’ surrounding Australia – Fiji, the Solomons, Bougainville, Mindanao, West Papua, East Timor, Maluku, Aceh, and Indonesia generally – should be reminder enough for most Australians as to their vulnerability and aloneness in this remote region. Australia’s only military ally of substance, the US, equivocated when put to the test (ie, East Timor), and our formal military alliances with countries of Asia have either been torn up (Indonesia), or are rather one-way arrangements (Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand).

Australia’s involvement in East Timor in 1999 marked a watershed in Australia’s relationship with Asia as a whole. Surprising at it may seem to many Australians, Asia was not at all impressed with the swaggering arrogance and jingoism it witnessed when Australian troops landed in East Timor in the manner of a ‘liberation force’. Many Asian leaders no doubt quietly asked themselves, "If it can happen to Indonesia, can happen to us?". Asian states find it extremely difficult to comprehend that Australia’s motives for intervening were purely ‘noble’, based upon a kind of high, selfless humanitarianism. Asia’s political leaders especially seem to find it impossible to believe that a nation can pursue aggressive military action on purely ‘moral’ grounds.[15]

Australian military adventurism in East Timor has opened up the real possibility of Australian involvement in other hotspots in its region, including Maluku, West Papua, and some troublesome specks in the Southwest Pacific. The display of force in East Timor, and the jingoistic chest-beating of Australians during this time, has led to question marks being placed over Australia’s long-term intentions by some Asian elites. As bizarre as it may have seemed a just a year ago, some Asians – Indonesians and Malaysians especially – worry about Australian expansionism into the region. During the height of the East Timor conflict, some Indonesians claimed that Australia wished to create a chain of vassal states out of Indonesia’s eastern provinces,[16] a kind of "Australasian Co-prosperity Sphere" with the Wallace Line[17] as its western frontier. This may well become a self-fulfilling prophecy as demands for Australian military assistance are made by surrounding states and separatist movements, based in part on the precedent set in East Timor.

To many eyes, Australia’s crude attempt to inject itself into the Asian discourse has been executed in the manner of a boorish, uninvited interloper, blind to the obvious differences. Asians are also very resentful towards the cultural supremacism displayed by Australia and Australians, particularly Asians in former European colonies. Australians are in fact highly resistant to change, and do not feel any need to compromise what they feel is a superior cultural outlook with that of an Eastern outlook, that most Australians, in moments of honesty, would consider subordinate and ultimately inferior.

For too many years perhaps, Australian policy towards Asia has been in the hands of ‘cultural denialists’, those who seek to deny the fundamental importance of culture in the behaviour of people and nations, frequently arguing that economics or class issues are of much greater substance than culture.[18] Australian perspectives and discourses that seek to explain Australia’s relationship with Asia in cultural terms are conspicuous by their absence. Yet it is in these very terms that Asia defines its relationship with Australia; it is culture that determines Australia’s political exclusion from Asia. Asia and Asians still very much identify themselves as being part of an Eastern civilisation and culture, separate and not fully comprehensible to mere Westerners. The ‘truth’ or otherwise of this is irrelevant; perceptions count for everything, which is rather unfortunate for those brave Australian academics who claim that "we have moved beyond the East versus West dichotomy"[19]: Asians clearly have not!

Australia can indeed influence Asia at many levels, proportionate to its relative size, but it should never expect to be an ‘equal’ partner. If Australia is to become an integral part of any regional grouping in the future, it will be one it has carved out for itself by projecting its own power into the region, limited though this may be. No amount of dialog with Asia will change Australia’s history and heritage, nor will it make much impression on Australia’s fundamental Western cultural outlook.

It has frequently been observed that Australia needs Asia, more than Asia needs Australia. Whilst Australia should always be prepared to participate in regional forums, it cannot expect to play any leadership or ‘insider’ role. Australia and Australians need to learn to live with their ‘odd man out’ status in this region.

Notes

[1] For the sake of brevity, in

this essay the term "Asia" and "Asian" refer specifically to East

Asia.

[2] S. Dalby (1996),

‘Continent Adrift?: Dissident Security Discourse and the Australian

Geopolitical Imagination’, Australian Journal of International

Affairs, Vol 50 No 1, 1996

[3] Dept of Foreign Affairs

and Trade (1997), In the National Interest: Australia’s Foreign and

Trade Policy White Paper, Parliamentary and Media Branch, Department

of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Barton: paragraph #8

[4] Gary Smith et al (1996),

Australia in the World: An introduction to Australian Foreign

Policy, Oxford University Press, Melbourne: 108

[5] Richard Leaver (1997), ‘Patterns

of dependence in post-war Australian foreign policy’ , in Richard Leaver

and Dave Cox (1997), Middling, Meddling, Muddling: Issues in

Australian foreign policy, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards: 89

[6] Smith (1996): 111-113

[7] These are views I recall from

issues of Asiaweek of the late 1980’s, and also directly from Malaysian

and Singaporean business and social acquaintances of that same time.

[8] For a similar account, see

also Michael Wesley (1997), "The politics of exclusion: Australia,

Turkey and definitions of regionalism", The Pacific Review, Vol.

10 No 4: 526

[9] Brian Toohey

(1997), ‘The experts divide over Asia’, The Australian Financial

Review, 13-14 December, 1997

[10] Noel Tracy (1997), "The APEC

dilemma: problems along the road to a new trade regime in the Pacific",

in Richard Leaver and Dave Cox (1997), Middling, Meddling, Muddling:

Issues in Australian foreign policy, Allen & Unwin, St Leonards:

143

[11] Wesley (1997): 539

[12] Wesley (1997): 532-535

[13] Richard Higgott

(1998),‘The International Relations of the Asian Economic Crisis: A

study in the politics of resentment’, paper presented at a conference

organised by the Asia Research Centre, Murdoch University, and the

Centre for International Studies, Yonsei University, Fremantle, 20-22

August, 1998.

[14] Wesley

(1997): 546

[15] I have tried

myself numerous times to explain Australia’s position on the issue of

East Timor to many seemingly well-informed and intelligent Asians over

the years, and especially this past year. The conversation invariably

returns to what Australia’s motive really was in intervening (eg, oil,

expansionism, elections, amongst others). And in fact, perhaps they are

right; after 23 years of watching Indonesian behaviour in East Timor,

Australians probably wanted to extract some satisfaction in the form of

revenge for the humiliation of being forced into the position of an

acquiescent spectator for so long.

[16] This is based on my own

observation of local Indonesian media reports over the past year since

Australia entered East Timor. The level of suspicion in Indonesia

towards Australia is extremely high, and Indonesian’s are generally

prepared to believe the worst about Australia and Australians without

need of evidence or facts. It is, in fact, now almost unpatriotic for

an Indonesian to consider Australia a ‘friend’.

[17] The Wallace Line is an

imaginary line passing between the islands of Bali and Lombok, and

Kalimantan and Sulawesi, which separates the Australasian and Oriental

biogeographical domains, and delineates the sharp break between Oriental

and Australian/Papuan fauna and landscape. (Eg, marsupials are only

found east of the Wallace Line.)

[18] Dick Robison and some of his

colleagues at the Asia Research Centre are worthy representatives of

this tendency, and of the new orthodoxy concerning Australia’s approach

to Asia that has taken hold over the past few years.

[19] Garry Rodan (2000), P269

Australia’s Engagement with Asia External Study Guide (2000), Murdoch

University, Semester 1 2000: 43

Gary Dean

Gary Dean