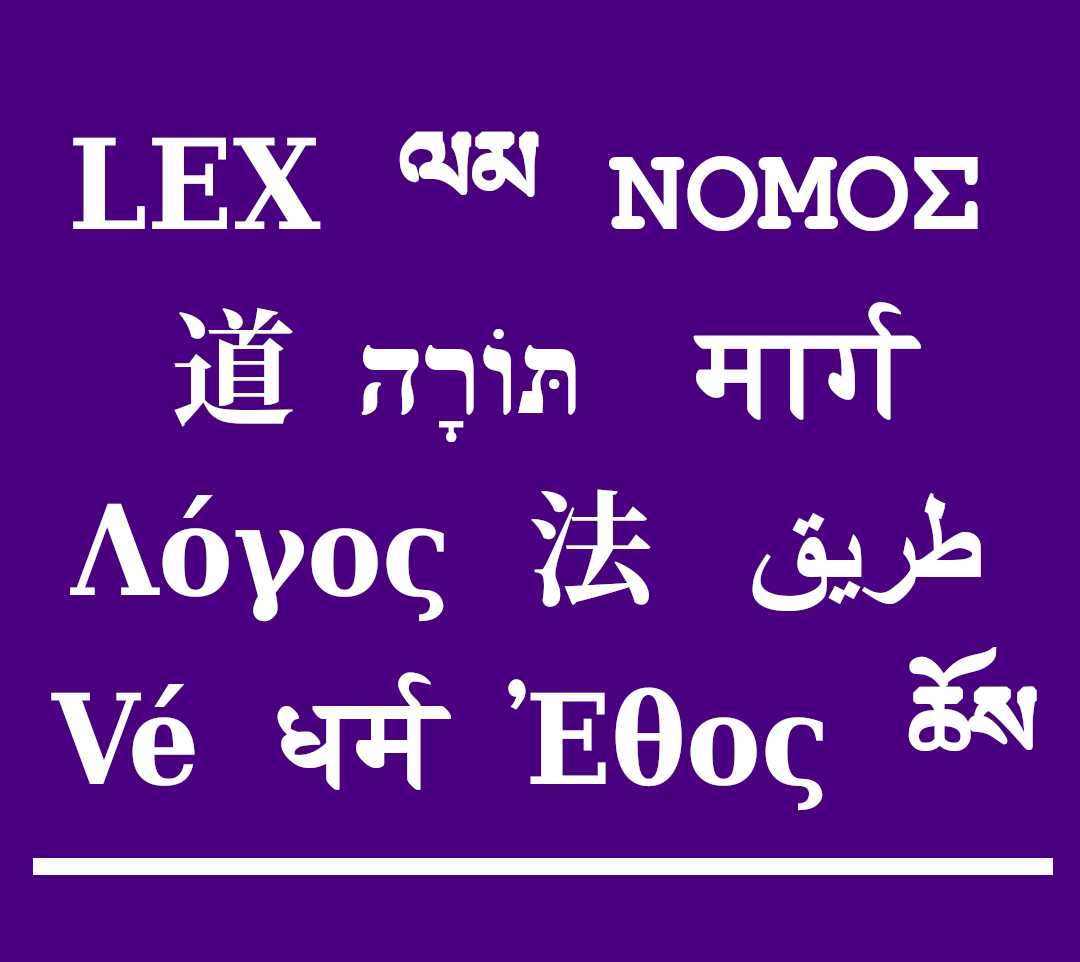

Defining Dharma

ways, paths, cultures, outlooks

The Etymology of ‘Dharma’

The word dharma is one of the most enduring and multifaceted terms in human thought, with deep roots in ancient Indian languages and cultures. While it is often associated with religious or spiritual traditions, its etymology reveals a concept that transcends doctrinal boundaries. Understanding the origin of the word provides a foundation for exploring its evolution into a dynamic framework for ethical living, social cohesion, and existential orientation.

Linguistic Roots

The term dharma originates from the Sanskrit root dhṛ (धृ), meaning “to hold,” “to support,” or “to sustain.” This root conveys the idea of that which upholds or maintains the structure of reality—whether cosmic, social, or individual. The noun dharma (धर्म) thus came to signify “that which holds together” or “that which maintains order.”

This etymological foundation is echoed in related Indo-European languages:

- Latin: firmus (firm, stable)

- Greek: thronos (seat, support)

- Lithuanian: derėti (to be suitable, fitting)

- English: firm, endure, truth (via Proto-Indo-European roots)

These linguistic parallels suggest that the concept of order, stability, and support is a shared cognitive structure across cultures, pointing to a deep evolutionary and cognitive basis for the emergence of ethical and social frameworks.

Early Usage in Vedic and Dharmic Traditions

In the earliest Vedic texts (circa 1500 BCE), dharma was closely associated with ṛta—the cosmic order that governed the natural and moral universe. Ṛta represented the principle of harmony that sustained the cycles of nature, the seasons, and the rituals that aligned human life with the cosmos. Over time, dharma absorbed and extended this meaning, becoming the term that governed not only cosmic order but also human duties and ethical conduct.

In later Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh traditions, dharma evolved into a central organizing principle:

- In Hinduism, it refers to the duties and responsibilities appropriate to one’s age, caste, and stage of life (varnashrama-dharma), as well as the universal moral order (sanātana dharma).

- In Buddhism, dharma (Pali: dhamma) denotes the teachings of the Buddha and the truth of reality as it is.

- In Jainism, dharma includes both moral duty and a metaphysical substance that enables motion.

- In Sikhism, it is associated with righteous conduct and devotion to truth.

Despite their doctrinal differences, these traditions converge on the idea of dharma as a force or principle that sustains both the individual and the collective, aligning human life with a greater order.

Dharma as an Adaptive Ethical Framework

From a secular and evolutionary perspective, dharma can be understood as an adaptive cultural response to the challenges of human social life. As a species, humans evolved in tightly knit groups where cooperation, fairness, and mutual support were essential for survival. The emergence of ethical codes—what we might call dharmas—served to stabilize group behavior, reduce internal conflict, and foster long-term cohesion.

The etymological idea of “support” or “holding together” resonates with the biological and psychological functions of moral systems. Ethical norms provide cognitive scaffolding for decision-making, emotional regulation, and social coordination. In this light, dharma is not merely a religious or metaphysical concept but a cultural technology that evolved to meet the demands of complex social living.

This view aligns with contemporary understandings in evolutionary biology and behavioral psychology, which emphasize the role of pro-social behaviors, empathy, and fairness in the development of human societies. The etymology of dharma thus reflects not only a linguistic history but also a deep biological and cultural logic.

Applications in Contemporary Contexts

In modern usage, particularly in secular dharmic frameworks, dharma is interpreted as:

- A personal ethical path or worldview that aligns one’s actions with values such as compassion, integrity, and responsibility.

- A collective framework for social justice, sustainability, and governance that supports the well-being of communities and ecosystems.

- A philosophical orientation that emphasizes impermanence, interdependence, and the cultivation of non-reactivity and mindfulness.

For example, the dharma of governance in a secular context might emphasize transparency, accountability, and participatory decision-making—principles that “hold together” a pluralistic society. The dharma of development may refer to technological innovation aligned with human dignity and ecological balance.

These contemporary applications reaffirm the etymological essence of dharma: to support, to uphold, to sustain. Whether in ancient ritual, moral philosophy, or modern policy, the term continues to serve as a guiding metaphor for living ethically within a complex and interconnected world.

Connections to Other Concepts

The etymology of dharma intersects with several other foundational concepts:

- Cosmic Order: In physics, the constants and laws that govern the universe mirror the ancient idea of ṛta and dharma as stabilizing forces.

- Biological Homeostasis: Just as organisms maintain internal balance, societies develop dharmas to maintain social equilibrium.

- Psychological Coherence: Ethical frameworks provide individuals with a sense of purpose and coherence, reducing existential anxiety and enhancing well-being.

These connections suggest that dharma, as a concept, operates at multiple levels—from the molecular to the societal, from the personal to the planetary.

The etymology of dharma reveals more than the origin of a word; it uncovers a deep structure in human cognition and culture—a structure oriented toward support, coherence, and ethical alignment. Whether in ancient hymns or modern secular philosophies, dharma continues to be a vital thread in the fabric of human meaning-making.

Beyond Etymology: ‘Dharma’ as an Idea

The term dharma is often introduced through its Sanskrit root dhṛ, meaning “to hold,” “to support,” or “to sustain.” This linguistic origin provides a conceptual foundation for understanding dharma as that which upholds order—cosmic, social, or personal. However, to reduce dharma to etymology alone is to miss its deeper significance. As an idea, dharma transcends language, religion, and tradition. It functions as a dynamic and adaptive framework for ethical orientation, social coherence, and existential navigation. It is not a static doctrine but an evolving response to the conditions of human existence.

Dharma as a Cognitive and Cultural Structure

From a secular and evolutionary standpoint, dharma can be understood as a cognitive-cultural adaptation—a mental and social structure that emerged to solve the perennial challenges of cooperation, conflict resolution, and meaning-making in complex human societies. As humans evolved in interdependent groups, the need for shared norms, values, and behavioral expectations became essential for group survival. Dharma, in this sense, is a product of cultural evolution: a framework that encodes and transmits adaptive behaviors across generations.

Rather than being fixed or universal, dharmas—plural and contextual—arise in response to specific ecological, historical, and social environments. They are not imposed from above but emerge from the lived interactions between individuals and their surroundings. This perspective aligns with contemporary understandings in anthropology, behavioral psychology, and cognitive science, which view moral systems as emergent, flexible, and deeply rooted in our neurobiology.

The Function of Dharma in Human Life

As an idea, dharma operates on multiple levels:

- Ethical Orientation: It provides a compass for navigating moral complexity, helping individuals discern what is appropriate, responsible, or life-affirming in a given context.

- Social Cohesion: It supports communal life by establishing shared expectations, reducing friction, and fostering trust and cooperation.

- Existential Meaning: It offers a framework through which individuals can interpret their place in the cosmos, respond to suffering, and cultivate purpose.

- Psychological Integration: It helps reconcile internal tensions—between impulse and restraint, autonomy and obligation, desire and discipline—thus contributing to mental coherence and well-being.

These functions are not exclusive to religious traditions. Secular dharmas—such as those found in humanism, ecological ethics, scientific rationalism, or civic responsibility—perform similar roles, guiding individuals and communities in the absence of metaphysical commitments.

Dharma as Process, Not Prescription

To understand dharma as an idea is to recognize its processual nature. It is not a rigid code but a living inquiry. It evolves through dialogue, reflection, and experimentation. It is shaped by the feedback loops between action and consequence, between intention and outcome, between individual agency and collective structure.

This view resonates with the notion of praxis in philosophy—the idea that ethical life is not merely about following rules but about engaging in reflective action. In this light, dharma is less about obedience to a static order and more about participation in a dynamic unfolding. It invites discernment, not dogma.

Examples of Dharma in Secular and Cultural Contexts

Across human cultures, dharma-like frameworks have emerged to guide behavior and sustain collective life:

- Ubuntu (Southern Africa): Emphasizing communal interdependence, Ubuntu articulates a dharma of relational ethics—“I am because we are.”

- Bushidō (Japan): The way of the warrior, rooted in honor, loyalty, and discipline, exemplifies a dharma of role-specific virtue.

- Scientific Integrity: In modern research communities, the commitment to truth, transparency, and peer accountability constitutes a dharma of epistemic responsibility.

- Environmental Stewardship: Ecological dharmas are emerging in response to planetary crises, emphasizing sustainability, intergenerational justice, and reverence for life.

These examples illustrate that dharma is not confined to ancient texts or religious institutions. It is a generative idea, continually reinterpreted in light of new challenges and insights.

Connections to Broader Philosophical and Scientific Views

The idea of dharma intersects with several contemporary discourses:

- Systems Theory: Dharma aligns with the principle of homeostasis—systems (biological, social, ecological) require balance and feedback regulation to sustain themselves.

- Evolutionary Psychology: Pro-social behaviors such as fairness, empathy, and cooperation—central to many dharmas—are seen as evolved traits that enhance group fitness.

- Neuroscience of Morality: The brain’s moral circuitry, including areas responsible for empathy and impulse control, underpins our capacity to engage with dharmic principles.

- Virtue Ethics: In philosophical traditions from Aristotle to Confucius, ethical life is understood as the cultivation of character and wisdom—an idea deeply resonant with dharmic practice.

These connections suggest that dharma is not merely a cultural artifact but a reflection of deeper patterns in human cognition, biology, and social organization.

To think of dharma as an idea is to engage with a concept that is at once ancient and urgently contemporary. It is the idea that life—individual and collective—requires orientation, coherence, and care. It is the recognition that ethical living is not a solved problem but an ongoing process of attunement to the realities of impermanence, interdependence, and complexity. In this sense, dharma is not a destination but a path—a way of being that holds us together, even as we change.

The Concept of a Dharma

The concept of a dharma is among the most enduring and adaptive frameworks for understanding ethical life, social order, and existential orientation. While often associated with South Asian religious traditions, the deeper logic of dharma transcends doctrinal boundaries. It is not a fixed rule or metaphysical commandment, but a dynamic structure—evolving, contextual, and responsive to the conditions of human existence. A dharma is best understood as a way or path—a culturally and biologically informed mode of living that sustains coherence within individuals and communities.

Dharma as a Functional Ethical Structure

At its core, a dharma functions as a stabilizing principle: it is that which “holds together” the elements of life—social, psychological, ecological, and existential. Derived from the Sanskrit root dhṛ, meaning “to hold” or “to sustain,” dharma is not a singular doctrine but a pluralistic and adaptive set of practices and orientations. These practices help individuals and groups navigate the complexities of life in a manner that is responsive to their particular time, place, and condition.

A dharma operates on multiple levels:

- Ethical guidance: It offers a framework for discerning right action in the face of moral ambiguity.

- Social cohesion: It provides shared norms and expectations that facilitate cooperation and reduce conflict.

- Psychological integration: It helps individuals align their internal states—desires, fears, impulses—with external responsibilities and values.

- Existential orientation: It situates individuals within a broader narrative of meaning, impermanence, and interdependence.

These functions are not exclusive to religious contexts. Secular dharmas—such as scientific integrity, environmental stewardship, or civic responsibility—serve similar roles in guiding behavior, fostering community, and grounding identity.

Dharmas as Products of Human Evolution and Culture

From an evolutionary perspective, dharmas can be seen as cultural technologies that emerged to solve the recurring problems of human social life. As a highly social species, humans evolved in interdependent groups where cooperation, fairness, and empathy were essential for survival. Over time, these pro-social tendencies were encoded into shared ethical systems—dharmas—that promoted group stability and individual flourishing.

Cultural evolution, like biological evolution, proceeds through variation, selection, and transmission. Dharmas that fostered resilience, adaptability, and cohesion were more likely to persist across generations. These systems were not designed from above but emerged from below, shaped by the lived experiences of communities responding to ecological pressures, technological changes, and social dynamics.

This evolutionary framing aligns with contemporary insights from anthropology, behavioral psychology, and neuroscience, which highlight the role of moral emotions, social learning, and environmental feedback in shaping human behavior. A dharma, in this light, is not a revelation but a refinement—a continually updated response to the challenges of living together.

Contextual and Plural: There Is No Single Dharma

There is no singular or universal dharma. Instead, there are dharmas—plural, contextual, and historically contingent. Each dharma reflects the conditions under which it emerged:

- A warrior dharma may emphasize courage, loyalty, and sacrifice.

- A healer’s dharma may prioritize compassion, attentiveness, and non-harm.

- A scientific dharma may be grounded in truth-seeking, skepticism, and methodological rigor.

- A civic dharma may focus on justice, participation, and the common good.

These dharmas are not mutually exclusive; they often intersect and inform one another. However, they are also subject to tension and conflict, especially when the values of one dharma clash with those of another. Navigating these tensions requires discernment, dialogue, and a willingness to adapt—qualities central to dharmic living.

Examples of Dharmas in Action

Across cultures and epochs, diverse dharmas have emerged to meet the needs of their societies:

- Ubuntu (Southern Africa): A relational dharma emphasizing mutual care—“I am because we are.”

- Bushidō (Feudal Japan): A martial dharma rooted in honor, discipline, and duty.

- Scientific ethics: A dharma of inquiry that values transparency, peer review, and intellectual humility.

- Environmental dharmas: Emerging in response to ecological crisis, these emphasize sustainability, interdependence, and reverence for life.

In each case, the dharma functions as a guide for action, a container for values, and a source of meaning. These dharmas are not static; they evolve in response to new challenges, technologies, and insights.

Dharma and Modern Thought

The concept of a dharma intersects with several contemporary philosophical and scientific frameworks:

- Systems theory: Just as biological and ecological systems require balance and feedback regulation, human societies develop dharmas to maintain homeostasis and resilience.

- Virtue ethics: In traditions from Aristotle to Confucius, ethical life is about cultivating character and wisdom—an idea deeply resonant with dharmic practice.

- Evolutionary psychology: Pro-social behaviors such as empathy, fairness, and cooperation—central to many dharmas—are seen as evolved traits that enhance group fitness.

- Neuroscience of morality: The brain’s moral architecture, including regions associated with empathy and impulse control, underpins our capacity to engage with dharmic frameworks.

- Existential philosophy: The tension between freedom and responsibility, between authenticity and obligation, mirrors the dharmic challenge of living ethically in a world without guarantees.

These connections suggest that the concept of a dharma is not merely a cultural artifact but a reflection of deeper patterns in human cognition, biology, and social organization.

A dharma is not a rulebook but a compass. It does not prescribe a single path but invites participation in an ongoing process of ethical attunement. It is a way of being that holds individuals and communities together, even as they change. Rooted in the realities of impermanence, interdependence, and complexity, the concept of a dharma remains a vital guide for living wisely and well in an uncertain world.

The Ancient Dharmic Philosophers

The ancient dharmic philosophers represent a diverse and profound lineage of thinkers who sought to understand the nature of reality, ethics, consciousness, and human flourishing. Emerging from the cultural and ecological conditions of early civilizations—particularly during the Axial Age (circa 800–200 BCE)—these philosophers articulated paths of living that responded to the existential and social challenges of their time. While rooted in specific traditions such as Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and early Indian rationalist schools, their insights resonate far beyond their historical contexts. They laid the groundwork for dharmas—adaptive, ethical frameworks that continue to shape human life across both religious and secular domains.

Dharma as a Philosophical Orientation

The term dharma derives from the Sanskrit root dhṛ, meaning “to hold,” “to support,” or “to sustain.” The ancient dharmic philosophers did not merely speculate about metaphysical truths; they developed ways of life that aimed to uphold coherence within the self, society, and cosmos. Their inquiries were not abstract exercises but embodied practices—ethical, contemplative, and social—that sought to align human behavior with deeper principles of order, impermanence, and interdependence.

These thinkers approached dharma not as a rigid doctrine but as a living path—responsive to the realities of suffering, desire, mortality, and the need for social harmony. They were not isolated mystics but participants in a broader human project: the cultivation of wisdom, virtue, and ethical discernment in a world marked by uncertainty and change.

Key Figures and Their Dharmas

Across the Indian subcontinent and neighboring regions, several figures stand out for their enduring contributions to dharmic thought. Each articulated a distinct dharma—a path of ethical and existential orientation—shaped by their cultural milieu and philosophical commitments.

Yājñavalkya and the Upanishadic Seers

Yājñavalkya, a central figure in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad, explored the nature of the self (ātman) and its relation to the ultimate reality (brahman). His dharma emphasized introspection, renunciation, and the pursuit of knowledge as a means to liberation. The Upanishadic seers collectively advanced a contemplative dharma rooted in inquiry, silence, and the recognition of impermanence.

Siddhartha Gautama (The Buddha)

The Buddha’s dharma emerged as a response to the pervasive suffering of human life (dukkha). Through the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, he offered a pragmatic framework for ethical conduct, mental cultivation, and insight into the impermanent and interdependent nature of existence. His teachings emphasized non-reactivity, mindfulness, and compassion—principles that continue to inform both spiritual and secular approaches to well-being.

Mahāvīra and the Jain Dharma

Mahāvīra, the 24th Tīrthaṅkara of Jainism, articulated a dharma grounded in ahiṃsā (non-violence), aparigraha (non-possessiveness), and satya (truthfulness). His path demanded rigorous ethical discipline and radical compassion for all living beings. The Jain dharma reflects a deep ecological sensibility and an uncompromising commitment to moral responsibility.

Kapila and the Sāṃkhya Tradition

Kapila, credited with founding the Sāṃkhya school, proposed a dualistic metaphysics distinguishing between puruṣa (consciousness) and prakṛti (matter). His dharma was one of discernment—liberation through the clear recognition of the difference between the seer and the seen. Sāṃkhya influenced later traditions by offering a systematic analysis of mind, matter, and liberation.

Patañjali and the Yoga Sutras

Patañjali synthesized contemplative and ethical practices into an eightfold path (aṣṭāṅga yoga) aimed at stilling the fluctuations of the mind. His dharma emphasized discipline (tapas), self-study (svādhyāya), and surrender (īśvarapraṇidhāna), culminating in samādhi—a state of meditative absorption. This framework continues to influence modern contemplative science and psychological well-being.

The Dharmic Function of Philosophy

The ancient dharmic philosophers were not merely metaphysicians or theologians; they were ethical architects. Their work served several critical functions:

- Ethical Orientation: They provided frameworks for discerning right action in a world of moral complexity.

- Social Cohesion: Their teachings helped stabilize emerging urban societies by articulating values such as compassion, duty, and restraint.

- Existential Navigation: They addressed the fundamental anxieties of human life—suffering, death, uncertainty—offering paths of meaning and resilience.

- Psychological Integration: Their practices cultivated self-awareness, emotional regulation, and cognitive clarity—capacities now affirmed by neuroscience and psychology.

These functions are not confined to religious contexts. Modern secular dharmas—such as scientific integrity, ecological stewardship, and civic responsibility—perform similar roles, echoing the adaptive logic of their ancient predecessors.

Connections to Modern Scientific and Philosophical Thought

The insights of the ancient dharmic philosophers align with and enrich contemporary discourses in several fields:

- Evolutionary Psychology: Many dharmic principles—such as empathy, fairness, and non-reactivity—correspond with evolved pro-social traits that enhance group survival and cohesion.

- Cognitive Science and Neuroscience: Practices like mindfulness and ethical reflection, central to dharmic traditions, are now recognized for their role in enhancing emotional regulation, attentional control, and well-being.

- Virtue Ethics: Like Aristotle and Confucius, dharmic philosophers emphasized the cultivation of character, wisdom, and ethical discernment over rule-based morality.

- Systems Theory: The dharmic emphasis on balance, feedback, and interdependence mirrors principles in ecology, biology, and cybernetics.

- Existential Philosophy: The dharmic engagement with impermanence, suffering, and freedom resonates with existentialist concerns about authenticity, responsibility, and the human condition.

These convergences suggest that dharmic thought is not a relic of the past but a living resource for navigating the complexities of modern life.

The Plurality and Adaptability of Dharmas

A defining feature of the ancient dharmic philosophers is their recognition of plurality. There is no single, universal dharma. Instead, there are many dharmas—contextual, evolving, and responsive to the conditions of life. This pluralism is not relativism but a recognition of complexity. A warrior’s dharma differs from that of a healer, a renunciate, or a ruler. Navigating these intersecting dharmas requires discernment, dialogue, and ethical sensitivity.

This adaptability is crucial in a world marked by rapid technological change, ecological crisis, and cultural pluralism. The dharmic legacy is not a fixed system but a dynamic process of ethical attunement—a way of being that sustains coherence amid impermanence.

The ancient dharmic philosophers articulated paths of living that remain vitally relevant. Their teachings offer not only metaphysical insights but practical frameworks for ethical action, social harmony, and existential clarity. Rooted in the biological and cultural realities of human life, these dharmas continue to evolve—guiding individuals and societies toward greater awareness, responsibility, and interconnection.

The Axial Age

The Axial Age (circa 800–200 BCE) marks a pivotal epoch in the evolution of human consciousness, ethics, and social organization. Coined by the German philosopher Karl Jaspers, the term refers to a period during which multiple, geographically dispersed civilizations underwent parallel transformations in thought. These transformations gave rise to enduring philosophical, religious, and ethical traditions that continue to shape human life. Rather than being a singular event, the Axial Age represents a convergence of responses to the existential, political, and ecological challenges of increasingly complex societies.

Historical Context and Cultural Conditions

The Axial Age emerged in response to a confluence of structural changes across Eurasia. Urbanization, the rise of city-states, expanding trade networks, and the breakdown of older tribal or ritualistic orders created new forms of social complexity. These transformations demanded new ethical frameworks capable of sustaining cohesion in societies no longer bound by kinship alone.

In this context, traditional mythologies and sacrificial systems began to lose their explanatory and normative power. What emerged in their place were reflective, dialogical, and often universalizing systems of thought—dharmas—that sought to address the human condition in more abstract, ethical, and philosophical terms.

Emergent Dharmas Across Civilizations

The Axial Age was not defined by a single doctrine or ideology but by the emergence of multiple dharmas—ways of life and thought—tailored to the conditions of their respective societies. These dharmas were not necessarily religious in the modern sense; they were ethical, existential, and often deeply secular in orientation, even when framed in theological language.

India: The Upanishadic sages shifted focus from ritual to introspection, emphasizing the unity of self (ātman) and ultimate reality (brahman). The Buddha articulated a dharma of non-reactivity, compassion, and mindfulness, grounded in the impermanence (anicca) of all phenomena. Jainism, through Mahāvīra, emphasized radical non-violence (ahiṃsā) and self-restraint.

China: Confucius responded to social disorder with a dharma of relational ethics, emphasizing filial piety, ritual propriety, and moral cultivation. Laozi and the Daoist tradition advocated for harmony with the natural order (Dao), spontaneity, and non-coercive action (wu wei).

Greece: Pre-Socratic philosophers and Socrates himself initiated a dharma of rational inquiry and ethical self-examination. Plato and Aristotle developed virtue-based ethics grounded in reason and the cultivation of character.

Persia and the Levant: Zoroaster introduced a moral dualism centered on truth and falsehood, influencing later Abrahamic traditions. The Hebrew prophets emphasized justice, compassion, and covenantal responsibility, laying the groundwork for ethical monotheism.

These dharmas, while diverse, shared a shift from external ritual to internal transformation, from tribal loyalty to universal ethics, and from mythic authority to reflective inquiry.

The Axial Shift as Cognitive and Evolutionary Adaptation

From a secular dharmic perspective, the Axial Age can be understood as a phase in human cultural evolution wherein new cognitive and ethical structures emerged to stabilize increasingly complex societies. As human groups grew beyond the scale of face-to-face communities, older mechanisms of cohesion—kinship, taboo, and sacrifice—proved insufficient. The dharmas of the Axial Age functioned as adaptive cultural technologies, enabling large-scale cooperation, moral regulation, and existential orientation.

These developments align with insights from evolutionary psychology and anthropology:

Pro-sociality and moral emotions: The dharmic emphasis on compassion, fairness, and non-violence corresponds with evolved traits that promote group cohesion and reduce conflict.

Narrative and abstraction: The shift toward universal ethics and metaphysical reflection reflects the human capacity for symbolic thought and narrative construction, which enables long-term planning and shared meaning.

Feedback and self-regulation: The emphasis on mindfulness, self-inquiry, and virtue cultivation mirrors the need for internal regulation in increasingly autonomous individuals embedded in complex societies.

The Dharmic Function of Axial Thought

The dharmas of the Axial Age served several interrelated functions:

Ethical orientation: They provided frameworks for discerning right action in a morally pluralistic world.

Social cohesion: They offered shared norms and values that could transcend tribal divisions and support larger political entities.

Existential navigation: They addressed suffering, death, and impermanence, offering paths of meaning and resilience.

Psychological integration: They cultivated self-awareness, emotional regulation, and the capacity for non-reactivity—qualities essential for navigating both internal and external complexity.

These functions remain relevant in contemporary secular dharmas, such as ecological ethics, human rights, scientific integrity, and civic responsibility.

Continuities with Modern Thought

The legacy of the Axial Age continues to inform modern philosophical and scientific discourses:

Virtue ethics: The dharmic emphasis on character and moral cultivation parallels Aristotelian and Confucian ethics, which remain influential in contemporary moral philosophy.

Systems theory: The dharmic concern with balance, interdependence, and feedback resonates with modern understandings of ecological and social systems.

Neuroscience and psychology: Practices like mindfulness and ethical reflection, rooted in Axial traditions, are now recognized for their role in enhancing cognitive flexibility, emotional well-being, and social intelligence.

Existential philosophy: The Axial inquiry into suffering, freedom, and meaning finds echoes in modern existentialist thought, which grapples with the human condition in a disenchanted world.

Secular humanism: Many contemporary ethical frameworks—emphasizing dignity, autonomy, and collective responsibility—can be seen as dharmic descendants of Axial Age innovations.

The Axial Age and the Plurality of Dharmas

A defining insight of the Axial Age is the recognition that there is no single, universal dharma. Instead, there are many dharmas—contextual, evolving, and responsive to the specific challenges of their time. This pluralism is not relativism but a recognition of complexity. The dharma of a monk differs from that of a ruler, a scientist, or a parent. Navigating these intersecting dharmas requires discernment, dialogue, and ethical sensitivity.

This insight is especially salient in the modern world, where global interdependence, technological acceleration, and ecological crisis demand new dharmas—adaptive, pluralistic, and grounded in both ancient wisdom and contemporary knowledge.

The Axial Age represents a threshold in the evolution of human consciousness—a period when reflective, ethical, and philosophical dharmas emerged to meet the demands of a changing world. These dharmas were not static doctrines but living inquiries into how to live wisely, ethically, and meaningfully in the face of impermanence, complexity, and suffering. Their legacy endures not as a set of answers, but as an invitation to continue the work of ethical attunement in every seculum that follows.

The Emergence of Dharmas

The emergence of dharmas represents a pivotal development in the evolution of human ethical life, social organization, and existential orientation. Far from being confined to religious or metaphysical systems, dharmas—understood as adaptive ways or paths of living—arise in response to the complex interplay of biological imperatives, ecological pressures, cultural innovations, and technological transformations. Across time and geography, dharmas have functioned as stabilizing frameworks that help individuals and societies navigate the challenges of cooperation, conflict, mortality, and meaning.

The Evolutionary and Cultural Foundations of Dharmas

Human beings are biologically predisposed to live in social groups. This evolutionary heritage—shaped by the demands of cooperation, empathy, and social regulation—provided the neurobiological substrate for the emergence of shared ethical norms. As hominins evolved larger brains and more complex social behaviors, they developed the capacity for symbolic thought, language, and storytelling. These capacities enabled the formation of cultural systems that encoded collective memory, moral expectations, and behavioral scripts—what we now recognize as dharmas.

The emergence of dharmas can be understood as a result of cultural evolution, operating through processes of variation, selection, and transmission. In early human communities, dharmas took the form of oral traditions, taboos, rituals, and kinship obligations. As societies grew in scale and complexity—particularly during the Neolithic and Bronze Ages—these informal systems were formalized into codes of conduct, religious doctrines, and philosophical schools.

The Axial Age (circa 800–200 BCE) marked a significant acceleration in this process. In India, China, Greece, and the Levant, thinkers independently articulated new dharmas that emphasized ethical self-cultivation, universal compassion, and reflective inquiry. These dharmas were not merely religious innovations; they were adaptive responses to the breakdown of older tribal systems and the rise of urbanization, political centralization, and existential anxiety.

Dharmas as Adaptive Ethical Frameworks

A dharma is not a rulebook but a living system—a functional structure that helps hold together the psychological, social, and ecological dimensions of life. Dharmas emerge to answer the question: How should we live, given the realities of our condition?

Key functions of dharmas include:

- Ethical guidance: Dharmas provide frameworks for determining appropriate action in complex and uncertain situations. They help individuals navigate moral ambiguity and conflicting priorities.

- Social cohesion: Dharmas establish shared norms and values that facilitate cooperation, reduce interpersonal conflict, and promote group identity.

- Psychological integration: Dharmas help individuals align their internal states—desires, fears, impulses—with external expectations and responsibilities, contributing to mental coherence and emotional regulation.

- Existential orientation: Dharmas offer narratives and practices that help individuals make sense of suffering, impermanence, and mortality.

These functions are not exclusive to spiritual traditions. Secular dharmas—such as scientific integrity, ecological responsibility, and civic participation—perform similar roles in modern societies.

Historical Examples of Emergent Dharmas

Throughout history, dharmas have emerged in response to specific social, ecological, and technological conditions:

- The Upanishadic Dharma: In ancient India, the Upanishads reoriented Vedic religion toward introspection and metaphysical inquiry, emphasizing the unity of self (ātman) and ultimate reality (brahman).

- Buddhist Dharma: The Buddha articulated a path grounded in mindfulness, ethical conduct, and non-reactivity, offering a pragmatic response to the problem of suffering (dukkha).

- Confucian Dharma: In China, Confucius proposed a relational ethics based on ritual propriety, filial piety, and moral cultivation—a dharma for sustaining social harmony in times of political fragmentation.

- Stoic Dharma: In Hellenistic Greece, the Stoics developed a dharma of rational self-governance, cosmopolitanism, and acceptance of fate, rooted in the idea of living in accordance with nature and reason.

Each of these dharmas emerged as a response to the breakdown or inadequacy of prior systems. They were not imposed from above but arose from the lived experience of individuals and communities seeking coherence in a changing world.

The Plurality and Contextuality of Dharmas

There is no singular or universal dharma. Rather, there are many dharmas—each shaped by the ecological, historical, and cultural conditions of its emergence. A dharma is always contextual, arising from a particular seculum—a temporal and social world with its own challenges and possibilities.

Examples of plural dharmas include:

- A warrior’s dharma: Emphasizing courage, loyalty, and sacrifice.

- A healer’s dharma: Centered on compassion, attentiveness, and non-harm.

- A scientist’s dharma: Grounded in truth-seeking, skepticism, and intellectual humility.

- An environmental dharma: Focused on sustainability, interdependence, and reverence for life.

These dharmas may intersect, overlap, or conflict. Navigating their tensions requires discernment, dialogue, and ethical sensitivity—qualities central to dharmic living.

Contemporary Applications and Reemergence

In the modern world, new dharmas are emerging in response to global challenges such as climate change, technological disruption, and political fragmentation. These include:

- Ecological dharmas: Emphasizing planetary stewardship, intergenerational justice, and systems thinking.

- Digital dharmas: Addressing the ethical use of artificial intelligence, data privacy, and algorithmic fairness.

- Civic dharmas: Promoting participatory governance, social equity, and democratic resilience.

- Scientific dharmas: Upholding epistemic responsibility, transparency, and the integrity of inquiry.

These secular dharmas reflect the same adaptive logic as their ancient counterparts: they emerge to hold together increasingly complex societies, to guide ethical behavior in novel environments, and to provide meaning in the face of uncertainty.

Connections to Broader Scientific and Philosophical Frameworks

The emergence of dharmas intersects with multiple domains of modern thought:

- Evolutionary biology and psychology: Pro-social behaviors such as empathy, fairness, and cooperation—central to many dharmas—are understood as evolved traits that enhance group survival.

- Neuroscience: The brain’s moral circuitry, including areas responsible for impulse control and empathy, underpins the human capacity for ethical reflection and dharmic practice.

- Systems theory: Dharmas function like regulatory systems, maintaining homeostasis in complex adaptive environments—whether social, ecological, or psychological.

- Virtue ethics: Like Aristotelian and Confucian traditions, dharmic frameworks emphasize the cultivation of character, wisdom, and moral discernment.

- Existential philosophy: The dharmic concern with impermanence, freedom, and responsibility resonates with existentialist inquiries into the human condition.

These connections suggest that dharmas are not relics of the past but emergent properties of human cognition, culture, and social organization.

The emergence of dharmas is a testament to the adaptive intelligence of human societies. As dynamic frameworks for ethical orientation, social cohesion, and existential navigation, dharmas arise wherever humans seek to live meaningfully within the constraints of biology, culture, and time. They are not fixed doctrines but living processes—ways of holding together the fragile coherence of life in a world that is always changing.

Common Characteristics of a Dharma

A dharma is not merely a religious or metaphysical concept but a dynamic framework for ethical living, social cohesion, and existential orientation. Rooted in the Sanskrit term dhṛ—meaning “to hold,” “to support,” or “to sustain”—a dharma functions as a stabilizing structure that helps individuals and communities navigate the complexities of life. While dharmas vary across cultures, traditions, and historical periods, they share certain fundamental characteristics that reveal their adaptive and integrative nature. These characteristics reflect deep patterns in human cognition, biology, and social organization.

Dharma as an Adaptive Ethical Framework

At its core, a dharma is a way of living that aligns personal behavior with broader ethical, ecological, and communal realities. It is not a rigid code but a flexible orientation that evolves in response to changing conditions. This adaptability is a key feature of all dharmas and is grounded in the biological and cultural evolution of Homo sapiens.

Human beings are social mammals who evolved in interdependent groups. The emergence of dharmas can be understood as a cultural response to the challenges of cooperation, conflict resolution, and meaning-making within increasingly complex societies. As such, dharmas function as adaptive ethical systems that facilitate:

- Group cohesion through shared norms and values

- Individual flourishing through psychological integration and moral clarity

- Ecological balance by aligning human behavior with natural systems

- Cultural continuity through the transmission of wisdom and practices across generations

These functions are not exclusive to religious traditions. Secular dharmas—such as scientific integrity, environmental stewardship, or civic responsibility—serve similar roles in contemporary societies.

Core Characteristics of a Dharma

Despite their diversity, all dharmas exhibit certain common features that define their role in human life:

Ethical Orientation

A dharma provides a framework for discerning appropriate action. It helps individuals navigate moral ambiguity by offering principles such as compassion, honesty, non-harm, and responsibility. This ethical orientation is not abstract but embedded in everyday practices, rituals, and decisions.

Contextuality and Plurality

There is no single, universal dharma. Instead, there are many dharmas—each shaped by specific ecological, historical, and cultural conditions. A dharma is always contextual, emerging from the lived realities of a particular seculum (a temporal and social world). For example:

- A healer’s dharma may emphasize care, attentiveness, and non-harm.

- A warrior’s dharma may prioritize courage, loyalty, and sacrifice.

- A scientist’s dharma may focus on truth-seeking, skepticism, and intellectual humility.

These dharmas are not mutually exclusive but often intersect, requiring discernment and ethical negotiation.

Psychological Integration

A dharma supports internal coherence by helping individuals align their thoughts, emotions, and actions. It provides a structure for managing impulses, cultivating virtues, and responding to suffering with resilience. Neuroscientific research on moral cognition and emotional regulation affirms the role of such frameworks in enhancing well-being and reducing reactivity.

Social Cohesion

Dharmas foster trust, cooperation, and shared identity within groups. They establish behavioral expectations and social roles, reducing conflict and enabling coordinated action. Anthropological studies of kinship systems, ritual practices, and moral codes reveal the centrality of dharmas in maintaining social order.

Existential Orientation

A dharma offers a way of making sense of life’s impermanence, uncertainty, and suffering. It provides narratives, symbols, and practices that help individuals locate themselves within a broader cosmological or ecological order. Whether through religious myth, philosophical reflection, or scientific understanding, dharmas address the human need for meaning.

Examples of Dharmas Across Cultures

The common characteristics of dharmas can be observed in diverse cultural expressions:

- Ubuntu (Southern Africa): A relational dharma emphasizing community, mutual care, and the interdependence of all beings—“I am because we are.”

- Bushidō (Japan): A martial dharma rooted in honor, discipline, and duty, guiding the ethical conduct of the samurai.

- Scientific Ethics: A secular dharma emphasizing transparency, peer review, and epistemic humility in the pursuit of knowledge.

- Ecological Dharma: Emerging in response to climate crisis, this dharma emphasizes sustainability, reverence for life, and intergenerational justice.

These examples illustrate the adaptability of dharmas to different environments and challenges, while maintaining their core function: to support life in all its complexity.

Connections to Scientific and Philosophical Discourses

The characteristics of dharmas align with insights from multiple domains of modern thought:

- Evolutionary Psychology: Pro-social behaviors such as empathy, fairness, and cooperation—central to many dharmas—are understood as evolved traits that enhance group survival.

- Neuroscience: The brain’s moral architecture, including regions responsible for empathy and impulse control, underpins our capacity to engage with dharmic principles.

- Systems Theory: Dharmas function like regulatory systems, maintaining balance and feedback within complex adaptive environments—whether social, ecological, or psychological.

- Virtue Ethics: Philosophical traditions from Aristotle to Confucius emphasize character cultivation and moral discernment, resonating with the dharmic focus on ethical development.

- Existential Philosophy: The dharmic concern with impermanence, freedom, and responsibility echoes existentialist inquiries into the human condition.

These convergences suggest that dharmas are not merely cultural artifacts but emergent properties of human cognition, biology, and social life.

A dharma is not a static doctrine but a living process—a way of being that sustains coherence amid impermanence. Its common characteristics—ethical orientation, contextual adaptability, psychological integration, social cohesion, and existential clarity—reflect the deep structures of human life. Whether ancient or modern, religious or secular, every dharma is a response to the question: How shall we live, given the conditions of our world?

Why Do Dharmas Exist?

Dharmas exist because human beings, as biologically social and cognitively reflective organisms, require structured ways to navigate the complexities of life. These structures—ethical, social, psychological, and existential—emerge not from divine command or abstract theory, but from the lived necessity of sustaining coherence within individuals and collectives. A dharma is a way of living that “holds together” the elements of life in a world marked by impermanence, interdependence, and uncertainty. The existence of dharmas reflects the evolutionary, cultural, and philosophical need for frameworks that support ethical behavior, social coordination, and meaningful orientation.

Evolutionary and Biological Foundations

Human beings evolved in tightly interdependent groups. Survival depended not only on individual fitness but on cooperation, empathy, fairness, and shared norms. These pro-social traits are deeply embedded in our neurobiology and behavioral repertoire. The emergence of dharmas—understood broadly as adaptive ethical frameworks—can be seen as a cultural extension of these biological imperatives.

From an evolutionary standpoint, dharmas function as stabilizing mechanisms:

- They regulate behavior within groups, reducing internal conflict and promoting cooperation.

- They encode strategies for managing resources, resolving disputes, and caring for vulnerable members.

- They provide cognitive templates for interpreting social roles, obligations, and consequences.

Neuroscience confirms that the human brain is wired for moral cognition. Regions associated with empathy, impulse control, and social reasoning enable the kind of ethical reflection that dharmas cultivate. In this light, dharmas are not arbitrary constructs but biologically grounded responses to the demands of group living.

Cultural Evolution and the Emergence of Dharmas

As human societies expanded beyond kin-based bands into villages, cities, and civilizations, the mechanisms of cohesion had to evolve. Oral traditions, rituals, and taboos gave way to more formalized dharmas—philosophical, legal, religious, and civic codes that could scale with complexity.

Cultural evolution operates through processes of innovation, selection, and transmission. Dharmas that fostered resilience, adaptability, and collective well-being were more likely to persist and spread. These dharmas were not static; they evolved in response to shifting ecological, technological, and political conditions.

The Axial Age (circa 800–200 BCE) represents a significant moment in this process. In India, China, Greece, and the Levant, thinkers articulated dharmas that emphasized ethical self-cultivation, universal compassion, and reflective inquiry. These were not merely religious revelations but adaptive responses to the breakdown of older tribal orders and the rise of complex, pluralistic societies.

Functional Roles of Dharmas

Dharmas exist because they serve multiple, interrelated functions essential to human flourishing:

Ethical Orientation: Dharmas provide guidance for discerning right action in morally ambiguous situations. They offer principles—such as non-harm, honesty, and responsibility—that help individuals navigate ethical complexity.

Social Cohesion: Dharmas establish shared norms and expectations that reduce friction and foster trust. They define roles, obligations, and boundaries, enabling coordination among diverse individuals and groups.

Psychological Integration: Dharmas help individuals align their internal states—desires, fears, impulses—with external responsibilities. They provide a coherent narrative that integrates emotion, cognition, and behavior.

Existential Meaning: Dharmas offer frameworks for interpreting suffering, impermanence, and mortality. They situate individuals within a broader cosmological, ecological, or philosophical order, providing a sense of purpose and orientation.

These functions are not exclusive to religious systems. Secular dharmas—such as scientific ethics, environmental stewardship, and civic responsibility—perform similar roles in contemporary societies.

Examples of Dharmas in Action

Across history and cultures, dharmas have emerged to meet the needs of particular communities and contexts:

Upanishadic Dharma: Rooted in introspection and metaphysical inquiry, this dharma emphasizes the unity of self (ātman) and ultimate reality (brahman), guiding individuals toward liberation through knowledge.

Buddhist Dharma: Grounded in mindfulness, compassion, and non-reactivity, the Buddhist path addresses the reality of suffering (dukkha) and offers a practical framework for ethical living and mental clarity.

Confucian Dharma: Emphasizing relational ethics, ritual propriety, and moral cultivation, Confucianism offers a dharma for sustaining social harmony in hierarchical societies.

Scientific Dharma: In modern contexts, the commitment to truth, transparency, and methodological rigor constitutes a dharma of epistemic responsibility.

Ecological Dharma: Emerging in response to planetary crisis, this dharma emphasizes sustainability, interdependence, and reverence for life.

These dharmas differ in form and content but share a common function: they help individuals and communities live coherently within their world.

Dharmas as Contextual and Plural

There is no singular, universal dharma. Instead, there are many dharmas—each shaped by the ecological, historical, and technological conditions of its emergence. A dharma is always contextual, arising from the lived realities of a particular seculum—a temporal and cultural world.

- A warrior’s dharma may emphasize courage and loyalty.

- A healer’s dharma may prioritize compassion and non-harm.

- A civic dharma may focus on justice, participation, and the common good.

These dharmas intersect and sometimes conflict. Navigating their tensions requires discernment, dialogue, and ethical sensitivity—qualities central to dharmic life.

Connections to Scientific and Philosophical Discourses

The existence and persistence of dharmas can be understood through multiple disciplinary lenses:

Evolutionary Psychology: Dharmas reflect evolved pro-social behaviors—such as empathy, fairness, and cooperation—that enhance group survival.

Neuroscience: The brain’s moral architecture supports the capacity for ethical reflection, impulse regulation, and empathy—functions cultivated by dharmic practice.

Systems Theory: Dharmas function as regulatory systems that maintain homeostasis in complex adaptive environments—whether social, ecological, or psychological.

Virtue Ethics: Philosophical traditions from Aristotle to Confucius emphasize character cultivation and moral discernment, resonating with the dharmic focus on ethical development.

Existential Philosophy: The dharmic concern with impermanence, freedom, and responsibility echoes existentialist inquiries into the human condition.

These convergences suggest that dharmas are not cultural anomalies but emergent properties of human cognition, biology, and social life.

Dharmas exist because human beings need frameworks that can hold together the fragile coherence of life in a world that is always changing. Whether ancient or modern, religious or secular, every dharma is a response to the perennial question: How shall we live, given the conditions of our world? They are not fixed commandments but adaptive pathways—ways of being that sustain ethical orientation, social harmony, and existential clarity amid the uncertainties of existence.

The Evolution of Dharmas

The concept of dharma—derived from the Sanskrit root dhṛ, meaning “to hold,” “to sustain,” or “to support”—has evolved from its ancient Indic origins into a multifaceted framework for ethical living, social organization, and existential orientation. While traditionally associated with religious and metaphysical systems, dharmas can be more broadly understood as adaptive cultural and ethical structures that arise in response to the conditions of human life. The evolution of dharmas reflects the interplay between biology, cognition, ecology, and culture, offering insight into how human beings have continually sought coherence, meaning, and stability in a world of impermanence and complexity.

Dharmas as Evolving Ethical Structures

Dharmas are not static doctrines but dynamic, context-sensitive frameworks. They emerge, adapt, and sometimes dissolve in response to the shifting needs of individuals and societies. This evolutionary character is not metaphorical—it is grounded in the biological and cultural processes that shape human behavior.

Human beings are a highly social and symbolically intelligent species. Our survival has depended on cooperation, communication, and the ability to coordinate behavior through shared norms. Dharmas, in this light, are cultural technologies—systems of meaning and practice that regulate behavior, reduce conflict, and promote group cohesion. They are not imposed from above but emerge through lived experience, social learning, and intergenerational transmission.

As societies become more complex—economically, politically, ecologically—so too do their dharmas. What begins as a set of kinship-based taboos or ritual obligations may evolve into philosophical systems, legal codes, or civic ethics. The evolution of dharmas is thus a reflection of cultural evolution itself: the process by which human groups adapt to their environments through symbolic and behavioral innovation.

Historical Phases of Dharmic Evolution

The evolution of dharmas can be traced through several historical inflection points, each representing a shift in the scale and complexity of human life.

Tribal and Early Agrarian Dharmas

In early human societies, dharmas were embedded in myth, ritual, and kinship. These frameworks regulated social roles, resource distribution, and conflict resolution. They were often animistic or shamanic, emphasizing harmony with nature and ancestral continuity.

Axial Age Dharmas

The Axial Age (circa 800–200 BCE) marked a profound transformation. In India, China, Greece, and the Levant, thinkers began to articulate abstract, universalizable dharmas grounded in ethical reflection, self-cultivation, and metaphysical inquiry. The Buddha’s path of mindfulness and compassion, Confucius’ relational ethics, the Upanishadic quest for self-realization, and the Stoic pursuit of virtue all emerged in this period. These dharmas responded to the breakdown of tribal orders and the rise of urbanization, political centralization, and existential anxiety.

Classical and Imperial Dharmas

As empires expanded, dharmas became institutionalized. In India, the concept of varnashrama-dharma codified social roles and duties based on caste and life stage. In China, Confucian dharma was integrated into state bureaucracy. In the West, Christian and Islamic dharmas shaped legal and moral norms. These imperial dharmas provided stability but also rigidity, often reinforcing hierarchies and suppressing dissent.

Modern and Secular Dharmas

The modern era, shaped by scientific revolution, industrialization, and global exchange, has given rise to new dharmas. These include:

- Scientific dharmas grounded in empirical inquiry, transparency, and peer accountability.

- Humanist dharmas emphasizing dignity, rights, and autonomy.

- Ecological dharmas oriented toward sustainability, interdependence, and planetary ethics.

- Civic dharmas focused on democratic participation, justice, and pluralism.

These secular dharmas are not devoid of depth or meaning; they are grounded in the same adaptive logic as their ancient counterparts. They offer frameworks for ethical living in a disenchanted, interconnected world.

Characteristics of Evolving Dharmas

Despite their diversity, evolving dharmas share several key characteristics:

- Contextuality: Dharmas arise in response to specific ecological, social, and historical conditions. There is no universal dharma—only dharmas appropriate to particular circumstances.

- Plurality: Multiple dharmas can coexist, reflecting the diversity of roles, identities, and challenges within a society.

- Adaptability: Effective dharmas evolve. They incorporate new knowledge, respond to feedback, and remain open to revision.

- Integrative Function: Dharmas align internal states (emotions, desires, values) with external structures (institutions, roles, environments), promoting psychological coherence and social harmony.

- Existential Orientation: Dharmas help individuals navigate suffering, impermanence, and mortality. They provide meaning without necessarily invoking metaphysical absolutes.

Examples of Dharmic Evolution in Practice

- Environmental Dharma: In response to ecological collapse, new dharmas are emerging that emphasize regenerative agriculture, planetary stewardship, and intergenerational responsibility. These dharmas draw on ancient wisdom (e.g., ahiṃsā, Daoist harmony) and modern science (e.g., systems ecology, climate modeling).

- Digital Dharma: With the rise of artificial intelligence, surveillance capitalism, and algorithmic governance, digital dharmas are being proposed to ensure ethical design, data privacy, and humane technology.

- Postcolonial and Decolonial Dharmas: In formerly colonized societies, dharmas are evolving to reclaim indigenous wisdom while integrating global knowledge. These dharmas aim to heal historical trauma and build inclusive futures.

- Neuroethical Dharma: Advances in neuroscience and psychology are informing dharmas that emphasize emotional regulation, non-reactivity, and contemplative practice—often aligned with mindfulness-based interventions and trauma-informed care.

Connections to Scientific and Philosophical Discourses

The evolution of dharmas resonates with several contemporary intellectual frameworks:

- Evolutionary Biology and Psychology: Pro-social behaviors—such as empathy, fairness, and cooperation—are seen as evolved traits that enhance group survival. Dharmas encode and amplify these traits.

- Neuroscience: The brain’s moral circuitry, including the prefrontal cortex and limbic system, supports the capacities cultivated by dharmic practices—such as impulse control, compassion, and reflective decision-making.

- Systems Theory: Dharmas function like homeostatic systems, regulating behavior and maintaining balance within complex adaptive environments.

- Virtue Ethics: Philosophers from Aristotle to Confucius emphasized character cultivation and practical wisdom—core elements of dharmic life.

- Existential Philosophy: The dharmic concern with impermanence, freedom, and responsibility echoes existentialist themes, offering paths of meaning without recourse to dogma.

The evolution of dharmas reflects the deep human need to live ethically, coherently, and meaningfully in a changing world. Far from being relics of the past, dharmas are living processes—adaptive responses to the conditions of life. Whether rooted in ancient traditions or emerging from modern challenges, dharmas continue to guide human beings toward lives of awareness, responsibility, and care.

Examples of Dharmas in Human Cultures

Across human history, cultures have developed diverse frameworks to guide ethical behavior, social organization, and existential orientation. These frameworks—referred to as dharmas in a broad, non-sectarian sense—are not fixed doctrines but adaptive ways of living that emerge in response to the conditions of a particular time, place, and society. While the term dharma originates in South Asian traditions, its underlying logic—of sustaining coherence, supporting life, and orienting individuals within a broader order—is a universal human phenomenon. Whether religious or secular, ancient or modern, dharmas serve as cultural technologies that help individuals and communities navigate the complexities of existence.

Ubuntu: A Relational Dharma of Interdependence

Originating in Southern Africa, Ubuntu is a dharma rooted in the philosophy that “I am because we are.” It emphasizes the interdependence of all people and the moral imperative to treat others with dignity, compassion, and reciprocity. Ubuntu is not a codified system but a lived ethic that shapes social behavior, conflict resolution, and communal identity. It played a significant role in post-apartheid reconciliation in South Africa and continues to inform community-based justice systems and educational models.

Ubuntu exemplifies a dharma that prioritizes relational ethics over individual autonomy. It reflects evolved human tendencies toward empathy, fairness, and cooperation—traits that enhance group cohesion and resilience. From a neurobiological perspective, this dharma aligns with the activation of mirror neurons and the limbic system in social bonding and moral emotions.

Bushidō: A Warrior’s Dharma of Honor and Discipline

In feudal Japan, Bushidō—the “Way of the Warrior”—emerged as a dharma for the samurai class. It emphasized virtues such as loyalty, courage, honor, and self-discipline. Bushidō was not merely a martial code but a philosophical orientation that shaped personal conduct, governance, and aesthetics. It integrated Zen Buddhist influences, Confucian ethics, and Shinto spirituality, forming a composite dharma that guided both battlefield behavior and daily life.

Bushidō illustrates how dharmas can be role-specific and context-bound. It functioned as a stabilizing force within a hierarchical society, offering a moral compass in a world marked by political instability and existential uncertainty. Its emphasis on discipline and restraint resonates with contemporary understandings of executive function and impulse control in behavioral psychology.

Confucian Ethics: A Civic Dharma of Harmony and Hierarchy

Confucianism, though not labeled as “dharma” in its own terms, constitutes a dharma in its structure and function. It offers a relational and hierarchical ethical system based on ren (benevolence), li (ritual propriety), and xiao (filial piety). Confucian ethics emphasize the cultivation of virtue through education, self-discipline, and respect for social roles.

This dharma emerged in response to the political fragmentation of the Warring States period in China and sought to restore social order through moral cultivation rather than coercive rule. It reflects a systems-oriented approach to governance and personal development, aligning with principles in systems theory and virtue ethics. Confucian dharma continues to influence East Asian societies in domains such as education, family structure, and public service.

Scientific Integrity: A Secular Dharma of Truth-Seeking

In modern secular contexts, the ethos of scientific inquiry constitutes a dharma grounded in truth-seeking, skepticism, and methodological rigor. Scientists operate within a framework that values transparency, peer accountability, and epistemic humility. This dharma is not enforced by religious authority but by communal norms, institutional practices, and the self-correcting mechanisms of the scientific method.

Scientific dharma reflects evolved cognitive capacities for pattern recognition, hypothesis testing, and social learning. It also embodies ethical commitments to honesty, openness, and the pursuit of knowledge for the collective good. In this sense, it serves both individual and societal functions—advancing understanding while regulating behavior through shared standards.

Environmental Stewardship: A Planetary Dharma of Interdependence

In the face of ecological crisis, new dharmas are emerging that emphasize sustainability, systems thinking, and reverence for life. These ecological dharmas draw from indigenous traditions, scientific ecology, and global ethics to articulate a path of planetary responsibility. They emphasize intergenerational justice, biodiversity preservation, and the recognition of human embeddedness within natural systems.

This dharma reflects a shift from anthropocentric to ecocentric worldviews. It aligns with principles of homeostasis in biology and feedback regulation in systems theory. Ecological dharmas challenge dominant paradigms of consumption and growth, offering instead a framework for regenerative living that honors complexity, limits, and interdependence.

Civic Responsibility: A Democratic Dharma of Participation and Justice

In pluralistic societies, civic dharmas have evolved to guide participation in democratic life. These include commitments to justice, equality, freedom of expression, and the rule of law. Civic dharmas are often enshrined in constitutions, legal systems, and public institutions, but they are also cultivated through education, civic engagement, and ethical discourse.

Civic dharmas function to uphold social cohesion in the absence of shared metaphysical beliefs. They rely on procedural norms, deliberative processes, and institutional trust. From a behavioral perspective, they harness pro-social tendencies such as fairness and reciprocity, while also requiring vigilance against tribalism, authoritarianism, and systemic injustice.

Artistic and Cultural Dharmas: Expression as Ethical Orientation

Artistic traditions often embody dharmas that guide expression, interpretation, and cultural transmission. Whether through music, dance, literature, or visual arts, these dharmas provide frameworks for exploring identity, emotion, and meaning. They can challenge dominant narratives, preserve collective memory, or offer solace in times of upheaval.

Cultural dharmas are neurobiologically grounded in the human capacity for symbolic thought, emotional resonance, and aesthetic appreciation. They serve psychological functions—such as catharsis, integration, and transcendence—while also shaping collective imaginaries and social values.

Dharmas are not confined to temples, scriptures, or philosophical treatises. They arise wherever human beings seek to live meaningfully, ethically, and coherently within their world. Whether expressed through indigenous wisdom, civic engagement, scientific inquiry, or artistic creation, dharmas reflect the deep structure of human life: our need for orientation, our capacity for cooperation, and our longing for coherence in a world of flux. By recognizing the diversity and adaptability of dharmas across cultures, we gain insight into the shared evolutionary and existential challenges that bind us—and the creative responses that continue to sustain us.

The dharma of the Samin of Java

The Samin of Java, also known as Sedulur Sikep, represent a unique and enduring dharma—an ethical and cultural way of life that emerged in response to the socio-political and ecological conditions of Dutch colonial rule in the late 19th century. Founded by Surontiko Samin (originally Raden Kohar), the Samin movement articulated a form of nonviolent resistance rooted in indigenous Javanese values, simplicity, and moral clarity. Far from being merely a protest movement, the Samin dharma constitutes a coherent worldview, one that continues to offer insights into the nature of ethical living, resistance, and human dignity in the face of systemic domination.

Historical Context and Emergence

The Samin movement arose in the teak forest regions of Central and East Java during a period of intensified colonial extraction. Dutch policies had increasingly restricted access to communal forests, imposed burdensome taxes, and disrupted traditional agrarian life. In this context, Surontiko Samin articulated a response that was not revolutionary in a militaristic sense but radical in its ethical refusal. His teachings rejected the legitimacy of colonial authority, not through violence, but through silence, non-cooperation, and the cultivation of an alternative moral order.

This dharma was not codified in scripture but transmitted orally through parables, aphorisms, and lived example. It emphasized honesty, nonviolence, self-sufficiency, and the rejection of greed and deceit. Samin’s followers refused to pay taxes, register land, or participate in state institutions, choosing instead to live quietly and autonomously within their own ethical framework.

Core Ethical Principles

The Samin dharma is defined by a constellation of ethical principles that function as both personal discipline and collective identity:

Nonviolence and Passive Resistance: The Saminists embodied a form of resistance that eschewed confrontation. Their refusal to comply with colonial demands was expressed through silence, ambiguity, and non-engagement rather than protest or rebellion.

Simplicity and Self-Sufficiency: Material accumulation and trade were viewed with suspicion, often associated with exploitation and dishonesty. The Samin emphasized subsistence agriculture, mutual aid, and minimal dependence on external systems.

Honesty and Integrity: Speech was to be measured, truthful, and respectful. Deceit, envy, and quarrelsomeness were seen as corrosive to both individual character and communal harmony.

Ecological Harmony: The Samin viewed land not as a commodity but as a living partner. Their relationship with the forest and soil was one of stewardship, not ownership—a view aligned with broader dharmic principles of non-possession (aparigraha) and interdependence.

Autonomy and Communal Solidarity: While deeply communal, the Samin dharma emphasized individual moral agency. Each person was responsible for their own conduct, yet bound by a shared ethic that rejected external domination.

The Samin as a Secular Dharma

Though often labeled a religious movement, the Samin dharma is better understood as a secular or post-metaphysical dharma. Surontiko Samin himself reportedly denied belief in a personal deity, heaven, or hell, instead affirming that “God is within me”—a sentiment resonant with Javanese mystical traditions but also with secular existential perspectives.

This inward orientation did not lead to solipsism but to a heightened sense of ethical responsibility. The Samin dharma did not rely on divine command or institutional authority; it emerged from lived experience, ancestral wisdom, and the imperative to live with dignity under oppressive conditions. As such, it exemplifies a dharma that is grounded in human biology, cultural memory, and ecological awareness rather than metaphysical dogma.

Connections to Other Dharmic and Philosophical Traditions

The Samin dharma shares affinities with other indigenous and philosophical dharmas across time and geography:

Gandhian Satyagraha: Both emphasize nonviolent resistance, moral clarity, and the power of ethical example over coercion.

Daoism: The Samin rejection of imposed authority and alignment with natural rhythms echoes Daoist principles of wu wei (non-coercive action) and harmony with the Dao.

Buddhism: The Samin emphasis on non-reactivity, simplicity, and ethical speech parallels Buddhist teachings on the Eightfold Path and the cultivation of mindfulness.

Virtue Ethics: Like the Aristotelian tradition, the Samin dharma focuses on character formation, moderation, and the development of moral discernment through practice rather than rule-following.

Systems Theory and Ecology: The Samin’s ecological sensibility aligns with modern understandings of complex adaptive systems, where sustainability depends on feedback, balance, and interdependence.

Evolutionary Psychology: The Samin dharma reflects evolved human tendencies toward fairness, empathy, and in-group cooperation. Their refusal to engage in exploitative systems can be seen as a defense of pro-social values against institutionalized predation.

Contemporary Relevance and Legacy

In the modern era, the Samin dharma continues to inspire environmental activism, indigenous rights movements, and critiques of industrial modernity. Samin communities in the Kendeng Mountains have resisted limestone mining projects, invoking their ancestral duty to protect the land. Their struggle is not framed in legalistic terms but in ethical ones: the land is not property but kin.

The Samin also challenge dominant narratives of progress and development. Their refusal to participate in consumer capitalism, bureaucratic governance, or formal education systems is not ignorance but a conscious dharmic choice—an insistence that another way of life is possible. In an age of ecological collapse, social fragmentation, and existential anxiety, the Samin dharma offers a model of resilience rooted in simplicity, integrity, and mutual care.

The dharma of the Samin of Java is a living testament to the human capacity for ethical self-organization in the face of domination. It is a dharma that emerges not from abstraction but from soil, silence, and shared suffering. As such, it remains a vital resource for reimagining how to live well—together, responsibly, and in harmony with the world that sustains us.

The TriDharma of Sumarah

The TriDharma of Sumarah is a contemplative and ethical framework rooted in the Javanese spiritual tradition of Sumarah, a path that emphasizes total surrender (sumarah) to the unfolding of life. Emerging in mid-20th century Indonesia, Sumarah developed as a response to the complexities of modernity, colonial trauma, and the search for a grounded, embodied spirituality. The TriDharma—consisting of Suwung (Right Thinking), Manembah (Right Feeling), and Tampa Pindha (Right Action)—offers a holistic path for aligning thought, emotion, and behavior in a way that fosters inner harmony and outer responsibility. It is not a metaphysical doctrine but a dharma: an adaptive, evolving way of ethical and existential orientation.

The Foundations of Sumarah

Sumarah, meaning “total surrender,” is a Javanese meditative and ethical tradition that invites practitioners to relinquish egoic control and align with the deeper rhythms of life. It does not prescribe dogma or ritual but encourages an inward attunement to what is called budi, or higher consciousness. The practice centers on deep relaxation, intuitive awareness, and the cultivation of ethical presence. Rather than striving for transcendence, Sumarah emphasizes immanence—the unfolding of insight and clarity through receptivity and stillness.