The New Order State and the Tempo Affair

A conflict of values

The sun began to set upon Indonesia’s corporatist ‘New Order’ state starting in the early 1990’s. Speculation about the presidential succession was rife, mainly due to President Soeharto’s increasing age and frailty, and such speculation was especially destabilising and damaging given Indonesia’s historical propensity to rather messy changes in leadership. Added to this was the ever-increasing seething discontent within the intellectual elite and some sections of Indonesia’s small middle class. Despite all this, the New Order state itself remained formidable, or at least gave an excellent impression of being so.

The banning of three weekly news magazines in 1994 marked the end of a short period of relative openness in the media in Indonesia. One magazine in particular, Tempo, wielded great influence amongst a section of the urban elite, representing values and a worldview which were in nearly every case diametrically opposed to those expressed by the New Order state, and by traditional Indonesian cultures more generally. The banning of Tempo marked the beginning of a drawn-out siege leading to the eventual – and predictably messy – demise of the New Order in May 1998.

Here I shall discuss the 1994 Tempo affair with particular emphasis on why actors within the New Order state reacted in the way that they did. Corporatism as a general concept shall first be described, before moving on to the particular New Order corporatism extant in the Indonesia of that period. The Tempo affair itself shall then be described, along with the reaction of the New Order state and several of its actors.

There is wide variation in the manner in which systems referred to as ‘corporatist’ operate. A mild, social-democratic form of corporatism is found, for example, in Scandinavian countries. At the other end of the scale are countries such as Indonesia under Soeharto, whose ‘New Order’ corporatism at times verged on the totalitarianism. Corporatism in whatever its form is characterised by the control of major social organisations by the state, with the aim of removing or suppressing social conflict, and fostering nationalism and national economic and social objectives. Corporatism in general reflects a sense of collectivism in social and economic affairs. It therefore contrasts with the more individualist liberal-capitalist economic models. While liberalism emphasises the primacy of the individual, corporatism emphasises the community and the social group. Thus, at a superficial level of analysis at least, liberalism and its associated values would seem to be the antithesis of corporatism.[1]

In nearly every case, corporatism is used a tool of national unity in which the entire economic resources of the nation are enlisted in the name of national economic progress. Individualism is subordinated to the ideological or national goals of the state, which gives greater emphasis to the ‘common good’ as opposed to the supposed rights of the private individual, especially in the arena of economics.[2] Thus, corporatism is strongly limited within defined national boundaries; it is inwardly focussed and tends towards parochialism.

At the core of corporatism is collectivism, the belief that collective human endeavour is of greater practical and moral value than individual self-striving, and that collective interests should prevail over individual interests. It is through the state that collective interests can be upheld with the threat of legal force.[3] Whereas liberals will make a distinction between the individual and society, the collectivist outlook sees the individual as being inseparable from society. Traditional, pre-industrial societies in particular stress the importance of the collectivity, social life and the community. In the contemporary context, such societies have sought to preserve these collectivist values in the face of the challenge from Western individualism.

Indonesia, despite paper-thin modernist veneers, is very much a traditionalist society and state. The cultures that comprise Indonesia are still very much characterised by collectivist values and by systems of patronage. Collectivism and patronage together stress the vertical axes of human relationships, in contrast to individualism and egalitarianism, which stress the horizontal axes. Indonesian patronage networks form the basis of virtually all social, political and economic relationships. Power distances between levels in the network are great, and flexibility of movement within the network restricted by obligation and responsibility to patrons and clients.[4]

The corporatist New Order state in Indonesia came into being in 1966 after what was effectively a military coup against Indonesia’s founding President, Soekarno, along with a bloody massacre of up to a million so-called ‘communists’. The New Order regime sought to co-opt every major power grouping within the Indonesian state, including the military, the Islamists, and the priyayi bureaucracy, but excluding the significant abangan stream that was seen as the basis of the Indonesian communist party (PKI). Whilst obviously collectivist in its orientation, the New Order was most profoundly anti-communist despite embracing concepts of ‘socialism without the class struggle’.[5] Like the European fascists, the New Order regime was fanatically dedicated to national unity and integration, and viewed with great suspicion notions of unity based upon social class that cut across national boundaries.

Thus, the New Order regime distrusted and feared both capital and labour interests within the Indonesian state. Social classes and groups within society are expected not to conflict with one another but rather expected to work in harmony for the common good and the national interest.[6]

The New Order state is imagined as a singular integral social structure, including all groups and members of society who are linked organically to one another within a web of interdependence.[7] Society is dissolved into and represented by the state.

Another important concept underlying the ideology of the New Order state is that of kekeluargaan, or ‘family-ness’. Traditional Southeast Asian family values play an important role in the wider political and social realm, dictating how relations between people are structured and maintained, and the protocols and conventions used in political and social communication. The very language of interpersonal social relations is the language of the family. Family titles, such as Bapak (‘father’) and Ibu (‘mother’), are also polite forms of address for figures of authority or for formally addressing persons of equal rank. Thus, authority figures of every kind, including and especially political leaders, are very much identified as parental figures, fitting well into the tightly hierarchical corporatist structure of the New Order.

Tempo was a weekly magazine established in 1971, born towards the end of the short-lived period of relative press freedom after the birth of the New Order. The first years of New Order rule have been described as “characterized by remarkable political ferment and free expression of ideas (except for former communists) after the constraints and fears of the late Sukarno era.”[8] As the New Order consolidated its power, however, it progressively tightened controls on expression and transformed the slogan “politics, no; development, yes,” a slogan which had become popular among groups dissatisfied with the increasingly polarized politics of the Sukarno era, into a rigid doctrine.[9]

With a circulation of 200,000 per edition, the magazine became one of Indonesia’s most popular. The magazine was directly modelled after the US Time magazine (‘Tempo’ roughly means ‘time’ in Indonesian) in the visual formats that it used, and more significantly, in the style of journalism employed. Although an Asian magazine, Tempo was very much a product of the West. It prided itself on its ‘hard-hitting’ investigative reporting, upon its ‘objectivity’, and upon the skill of its writers. According to its boosters, Tempo had become “an essential reading material especially for critical minds” providing the nation “with accurate information and lively commentaries.”[10]

With such qualities, it should be no surprise that Tempo was held up by its admirers in the Western media as an example of a free press in action. The magazine won praise from foreign publications, and several major ‘free speech’ awards from international (ie, Western) media organisations, and its editor, Goenawan Muhamad, lauded with similar recognition and praise. World Press Review honoured Goenawan as ‘International Editor of the Year’, the award going “to an editor outside the United States in recognition of enterprise, courage, and leadership in advancing the freedom and responsibility of the press, enhancing human rights, and fostering excellence in journalism.”[11] In others words, for everything that is perceived as being good and wholesome about liberal Western society. He has also been awarded the Harvard University Nieman Fellowship for journalism and the Press Freedom Award of the Committee to Protect Journalists.

Goenawan’s background is most untypical for the average Indonesian. In fact, in many respects he is quite culturally alienated from the mass of ordinary Indonesians, sharing much more in common with the average Westerner than with the average Indonesian. The very fact of his education isolates him as ‘different’ within the context of Indonesia; his overseas education isolates him even further. Goenawan studied at the College d’Europe in Belgium obtaining a postgraduate degree in political science.

George J. Aditjondro, a now well-known Indonesian dissident, also worked as a journalist for Tempo from its inception until 1979. He fled Indonesia in 1995 to escape a political trial for articles he wrote about Soeharto-linked businesses. Similarly lauded by the West, he now teaches Sociology of Corruption at the University of Newcastle, Australia.

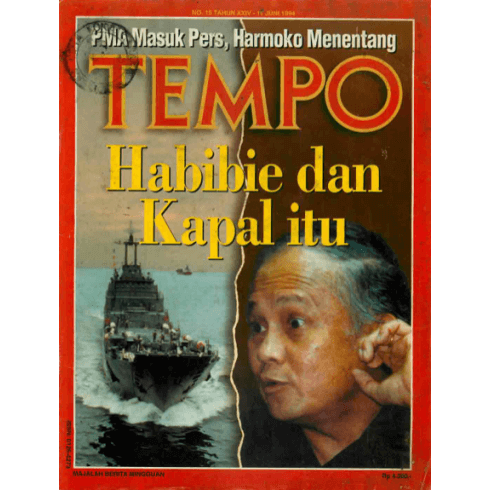

In June 1994, Tempo reported on allegations of corruption in the matter of the purchase of 39 warships from the mothballed East Germany navy. This report caused the Indonesian government great alarm. The report implicated the Minister of Research & Technology, BJ Habibie, President Soeharto’s protege, accusing him of corruption in the purchase of the ships and their refurbishment. The then Minister for Finance, Mar’ie Muhammad, on the other hand, was later to become known as a ‘cleanskin’ and whistleblower, and may well have been responsible for bringing the matter to the attention of Tempo. Unusually, Soeharto himself railed publicly about this report, accusing Tempo of jeopardising national security by provoking political controversy.[12]

Tempo’s publication licence was promptly revoked by the Ministry of Information, Harmoko, it is said on the direct orders Soeharto. Tempo brought the case to the courts for appeal. Surprisingly Tempo won in the first, and second level courts in 1995. But, as expected after more than a one year process in the courts, in the final ruling in June 1996 by the Supreme Court, Tempo lost, putting an end to its hope to ever publish the magazine again.[13]

The government gave Tempo’s licence to a new magazine, Gatra, which was supported by a well-connected and government-backed business tycoon, to provide alternative employment for Tempo people. The new magazine closely aped the format and style of its predecessor, however was naturally much more considerate towards the sensitivities of the state and its actors.

For the Indonesian intelligentsia and the tiny Indonesian middle class, the news came as a shock. Students took to the streets, and prominent local and international figures appealed to cancel the revocation, to no effect. According to internal marketing surveys, a majority of Tempo’s readers were university graduates, living in urban areas, and employed as civil servants, managers, and other professional occupations.[14] This, in a country where to aspire to a university education is almost like aspiring to be an astronaut.

As Liddle succinctly puts it, “Goenawan’s individualism runs directly counter to the state’s collectivism.”[15] His central moral and intellectual commitment is to the individual, and to concepts of individual self-mastery and self-knowledge.[16] He laments: “… we are still afraid of I. We feel more secure with We.”[17]

Goenawan and his journalistic colleagues inhabit a kind of high culture island that is foreign and forbidding to the vast majority of Indonesians, especially in the rural areas where most of the population is situated.[18] Goenawan himself acknowledges this great distance between modern and traditional Indonesia, and his own personal separation from his traditional roots, but claims that he is willing to trade this for the ‘freedom’ that modern Western liberalism gives him.[19] The social gap between the individualist intellectuals and the collectivist masses is very wide indeed.

Nearly all of Tempo’s weekly distribution was limited to Jakarta.[20] However, despite its highly limited geographic and demographic distribution, Tempo was one of the more important moulders of elite opinion, and Goenawan himself an important contributor.

So it was that on the 21st of June, 1994, a period of apparent keterbukaan (‘openness’) in Indonesia came to an abrupt end. And Tempo was not alone; two other lesser but comparable news magazines, Editor and DeTik, also had their publishing licences revoked (which is to say, they were banned). The three were accused, among other things, of violating Indonesia’s “journalistic code of ethics.” In particular, Tempo, respected widely for its liberal independence, was accused of not having “reflected the life of a sound press.”[21] Whilst the initial excuse for the bannings was the reportage surrounding the case of the East German warships, the bannings seem to have been part of a much wider crackdown upon dissent within Indonesian intellectual society. The challenges presented by these magazines were much wider than mere issues of the day; these magazines presented viewpoints and worldviews completely at odds with those of the Indonesian New Order state. The issue of the East German warships merely provided the trigger for the crackdown.

Soeharto correctly surmised that the banning of these magazines would not cause any meaningful political backlash. Despite the howls of protest from sections of the educated Indonesian elite, and similar howls from outside the country, Soeharto was secure in the fact that this would have no effect upon his constituencies: the peasantry, the bureaucracy, and the armed forces. The actual significance of the banning of Tempo as a political moment has been highly exaggerated both inside and outside Indonesia by those holding liberal Western worldviews. Both from the viewpoint of the New Order state, and from the viewpoint of the vast majority of Indonesians whose culture expresses strong collectivist values, the banning of Tempo was of little or no importance.

Some academics suggest that the bannings led to ‘massive’ protests around the country,[22] but closer inspection reveals that participants in these demonstrations numbered in the mere hundreds, and in nearly every case consisted mainly of university students. Whilst it is true to say that to demonstrate in 1994 took a good deal more courage than in 1998, still, the numbers and composition of these demonstrations tell the real story.

The values expressed by Tempo cut across virtually everything that New Order corporatist state represented. Its personnel were comprised of highly educated people who looked to the West for their political values, and aspired to modernity in its Western liberal form. It was not just that the New Order state was intolerant of criticism on particular issues; it was much more intolerant towards a worldview which reversed the flow of power and which cut away at the foundations of the entire collectivist social and political foundations of the system. At the heart of the conflict between the New Order state and Tempo was a conflict of cultures. Individualist, Western perspectives throw a spanner in the works of authoritarian collectivist worldviews.

Notes

[1] Andrew Heywood (1998), Political Ideologies: An Introduction (2nd edition), MacMillian, London: pg 223

[2] Heywood (1998): pg 222

[3] Heywood (1998): pg 107

[4] Richard Mead (1998), International Management: cross-cultural dimensions (2nd edition), Malden, Blackwell Publishers: pg 262

[5] David Reeve (1990), ‘The Corporatist State: The Case of Golkar’ in Arief Budiman (1990) State and Civil Society in Indonesia, Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, Monash University, Clayton: pg 164

[6] Heywood (1998): pg 226

[7] Reeve (1990): pg 162

[8] Jamie Mackie & Andrew MacIntyre (1994), “Politics,” in Indonesia’s New Order: The Dynamics of Socio-Economic Transformation, Allen & Unwin, St. Leonards: pg 12.

[9] Human Rights Watch (1998), “Academic Freedom In Indonesia: Dismantling Soeharto-Era Barriers”, at http://www.igc.org/hrw/reports98/indonesia2/Borneote.htm

[10] Saiful B Ridwan (1998), “From Tempo to Tempo Interaktif: an Indonesian media scene case study”, Tempo Interaktif, PT Grafiti Pers, Jakarta.

[11] Charles Stokes (1998), “International Editor of the Year”, World Press Review, Stanley Foundation, New York at http://www.worldpress.org/IEY98.htm

[12] David T Hill (1994), The Press in New Order Indonesia, UWAP-ARC Murdoch, Perth: pg 41

[13] Ridwan (1998)

[14] Goenawan Muhamad (1991), personal interview quoted in R. William Liddle (1996), Leadership and Culture in Indonesian Politics, Allen & Unwin, Sydney: pg 176

[15] R. William Liddle (1996), Leadership and Culture in Indonesian Politics, Allen & Unwin, Sydney: pg 166

[16] Liddle (1996): pg 146

[17] Goenawan Muhamad (1992), ‘Aku’, Tempo XXII, No 29 (19 Sept): pg 39 quoted in Liddle (1996) pg 147

[18] Liddle (1996): pg 162

[19] Goenawan Muhamad (1972), Portrait of a Young Poet as Malin Kundang, Pustaka Jaya, Jakarta.

[20] Liddle (1996): pg 161

[21] Pen American Centre (1998), ‘The Press in Indonesia’ at http://pen.org/freedom/asia/indonesia/indo3.html

[22] Hill (1994): pg 42