“I like ideas about the breaking away or overthrowing of established order. I am interested in anything about revolt, disorder, chaos, especially activity that seems to have no meaning. It seems to me to be the road towards freedom.” – Jim Morrison

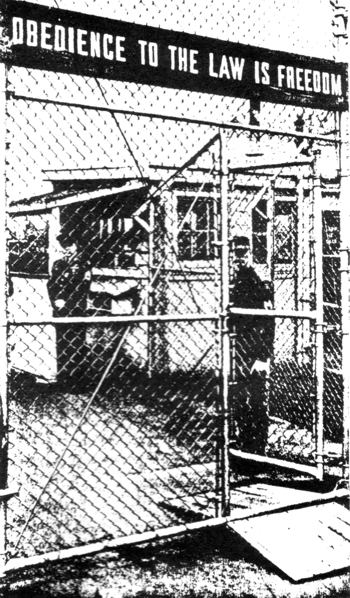

‘Obedience to the Law is Freedom’. Thus declared a sign hung over a gateway to a US army base in New Jersey in 1969. Of course, such a statement could be critically analysed on many levels and given a wide variety of interpretations. At its crudest, in the context of the Cold War environment of that time, one interpretation could go like this: “You must Obey Our Law. Disobedience to Our Law means you are a Communist, and Communists are the Enemies of Freedom”. (In the contemporary context “communist” could be replaced with “muslim”.)

Obedience to authority was the theme of Milgram’s experiment, which clearly demonstrated the disturbing tendency of people to obey bureaucratic authority in spite of what would seem to be obvious and serious offronts against common morality.

As individuals, we can tell ourselves that we have a moral right to kill

another individual in order to defend our own life. Law courts in most

nations frequently accept the plea of ‘self-defence’ in some murder

cases, reinforcing this moral belief within societies. However, what

happens when this commonly accepted morality is extrapolated to the

level of the group (nation state, racial or religious group, etc)? It

needs to the remembered that Homo erectus are not solitary

beings, but rather social animals; we as individuals cannot function

properly in isolation, despite what modern capitalist culture may

encourage us to believe.

As individuals, we can tell ourselves that we have a moral right to kill

another individual in order to defend our own life. Law courts in most

nations frequently accept the plea of ‘self-defence’ in some murder

cases, reinforcing this moral belief within societies. However, what

happens when this commonly accepted morality is extrapolated to the

level of the group (nation state, racial or religious group, etc)? It

needs to the remembered that Homo erectus are not solitary

beings, but rather social animals; we as individuals cannot function

properly in isolation, despite what modern capitalist culture may

encourage us to believe.

What happens if, say, New Zealand invades Australia. Does this give every Aussie the moral right to kill every Kiwi in order to defend their nation? When tribes are truly mobilised for war, surely there can be no ‘innocents’ or ‘non-combatants’. The contrived gentleman’s agreement on the ‘rules of war’ as enshrined in the Geneva Conventions are nothing more than imperial European guilt-trips, attempting to deny the reality and the horror of human warfare, and by extension, the human condition. War is not cricket.

On the other hand, when an atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, killing hundreds of thousands of non-combatant Japanese, could ordinary US citizens be held collectively responsible for not taking the strongest possible action to prevent such a tragedy occurring again in Nagasaki? Or perhaps, was the propaganda environment in the US at that time such that to voice the slightest doubt, opposition or moral outrage to the bombing would be considered treason? Could it be said that millions of US citizens chose patriotism before morality, and are therefore every bit as guilty of unimaginable brutality as the German people were for the Jewish holocaust? My answer, for what it is worth, is ‘yes’, they were indeed every bit as guilty, notwithstanding decades of heavily slanted, righteous propaganda pumped out of Hollywood post ‘World War II’.

Of course, in war, it is the victors who write its history, and the

victors who determine the pseudo-law used to exact revenge upon the

losers, by the use of material reparations for war damage to the

victor’s property, and by the ritual murder of those deemed guilty of

‘war crimes’. Needless to say, the pilot of Enola Gay never stood

as an accused in a war crimes court. If he did, what would his defence

be? Without much doubt, it would be “I was only doing my duty for my

country”, or perhaps “I was only following orders”, or “My commanding

officer made me do it. I had no choice.” In other words, the pilot would

attempt to transfer moral responsibility to those who ordered him to

drop the bomb, despite the fact that he would have been aware that

hundreds of thousands of ‘non-combatants’ – the old and sick, mothers

and their children, and plain, ordinary everyday folk – would die as a

direct consequence of his personal action.

Of course, in war, it is the victors who write its history, and the

victors who determine the pseudo-law used to exact revenge upon the

losers, by the use of material reparations for war damage to the

victor’s property, and by the ritual murder of those deemed guilty of

‘war crimes’. Needless to say, the pilot of Enola Gay never stood

as an accused in a war crimes court. If he did, what would his defence

be? Without much doubt, it would be “I was only doing my duty for my

country”, or perhaps “I was only following orders”, or “My commanding

officer made me do it. I had no choice.” In other words, the pilot would

attempt to transfer moral responsibility to those who ordered him to

drop the bomb, despite the fact that he would have been aware that

hundreds of thousands of ‘non-combatants’ – the old and sick, mothers

and their children, and plain, ordinary everyday folk – would die as a

direct consequence of his personal action.

Chains of command, the essence of hierarchical, bureaucratic authority,

serve as systems for transferring power and responsibility ever upward

towards the pinnacle of the pyramid, towards that single individual who

is ‘ultimately responsible’, at least in theory. Of course, this single

paramount individual will frequently pass moral responsibility to some

overriding concept or morality which, he/she may claim, has been

collectively agreed to, for instance the principles or ideology of a

nation state, a body of law, or a religious teaching. Human society

therefore finds it possible to excuse apparent immorality on the basis

of some alleged collective agreement, principle, or Greater Good. This,

however, assumes that the bureaucratic authority is pure, and untainted

by the presence of conflicts within the command chain, and by the

absence of competing command chains. As Milgram has correctly pointed

out, “conflicting authority paralyses action” and “the

rebellious action of others severely undermines authority.” To an

extent, it seems that the existence of choice puts the individual back

in command, and conflicting authority opens the possibility of this

choice.

Chains of command, the essence of hierarchical, bureaucratic authority,

serve as systems for transferring power and responsibility ever upward

towards the pinnacle of the pyramid, towards that single individual who

is ‘ultimately responsible’, at least in theory. Of course, this single

paramount individual will frequently pass moral responsibility to some

overriding concept or morality which, he/she may claim, has been

collectively agreed to, for instance the principles or ideology of a

nation state, a body of law, or a religious teaching. Human society

therefore finds it possible to excuse apparent immorality on the basis

of some alleged collective agreement, principle, or Greater Good. This,

however, assumes that the bureaucratic authority is pure, and untainted

by the presence of conflicts within the command chain, and by the

absence of competing command chains. As Milgram has correctly pointed

out, “conflicting authority paralyses action” and “the

rebellious action of others severely undermines authority.” To an

extent, it seems that the existence of choice puts the individual back

in command, and conflicting authority opens the possibility of this

choice.

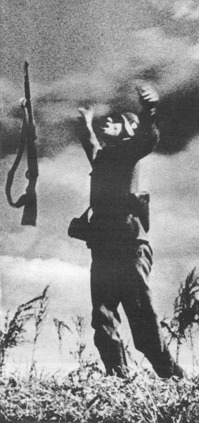

Milgram also asserted that “the experimenters physical presence has a

marked impact on his authority.” This brings to mind the apocryphal

stories about two soldiers from opposing camps who stumble upon each

other on the battlefield. They eye each other, and possibly see their

own reflection; they are each mere men, scared and human. They decide

not to shoot, but rather silently back away from each other. They return

to their respective camps, telling no one what happened. Whilst there

are many variations to this basic story, what always remains is the

element of the individual making a personal moral choice in opposition

to his assigned responsibility to his collective. The subtext to this

story is this: if one of the soldiers had not been alone, they would

have made a very different choice: they would have attempted to kill the

‘enemy’ soldier. The presence of a comrade changes the story completely.

It is no longer possible to merely slip quietly away, and pretend

nothing has happened. There is now a perceived obligation to obey, to

submit personal morality to the authority of the collective.

Milgram also asserted that “the experimenters physical presence has a

marked impact on his authority.” This brings to mind the apocryphal

stories about two soldiers from opposing camps who stumble upon each

other on the battlefield. They eye each other, and possibly see their

own reflection; they are each mere men, scared and human. They decide

not to shoot, but rather silently back away from each other. They return

to their respective camps, telling no one what happened. Whilst there

are many variations to this basic story, what always remains is the

element of the individual making a personal moral choice in opposition

to his assigned responsibility to his collective. The subtext to this

story is this: if one of the soldiers had not been alone, they would

have made a very different choice: they would have attempted to kill the

‘enemy’ soldier. The presence of a comrade changes the story completely.

It is no longer possible to merely slip quietly away, and pretend

nothing has happened. There is now a perceived obligation to obey, to

submit personal morality to the authority of the collective.

‘Obedience to the Law’ is an enslavement to the moral dictates and tyranny of the collective, whether in the guise of an army, a nation-state, a religion, a square-dance, or any of the multitude of structures both great and small which attempt to collectivise and structure human activity in all its forms. Therefore the only true individual freedom must come as a consequence of conscious disobedience to the law: only then is individual morality and individual choice truly expressed. Anarchy rules, ok?