To trade is human. Like the ability to communicate abstract ideas, trade is one of those activities that differentiates Homo sapiens from the rest of the animal world. And trade is more than just a mere exchange of surplus; its social and political impact is profound binding both families, tribes and nation-states into intricate webs of human intercourse. These ever widening circles of trade interaction encompass the world within a vast network of patronage, obligation and interdependency.

It is not possible to separate economics from its social and political consequences. Throughout history trade has been an important driving force, impacting upon societies - for better and for worse - throughout the entire world. Perhaps more than any other region on Earth, Southeast Asia has felt the driving force of economics transform its social and political structures, absorbing as it has strong cultural impacts from external trade powers starting with India and China, the Middle East, Europe, the United States and Japan. As local peoples enter into the wider circles of contact they must inevitably make adjustments to their own worldviews.[1]

Traditionally, Southeast Asian cultures emphasise the unity or synthesis of the social, economic, political, and religious spheres. Such an all-encompassing lens is an impractical analytical tool, so it is necessary to attempt to use only one of these spheres without losing sight or consciousness of the other spheres and their close interconnectedness. Today, when we speak of ‘the world’, we more often than not speak using the vocabulary of economics. Until recently the average Southeast Asian would think of ‘the world’ in purely religious or mystical terms.[2]

The economic history of Southeast Asian can be roughly divided into seven phases: the early, pre-empire period; the period of the great maritime trading states; the period of the European advance; the period 1870-1940; the post-independence period; the ‘economic miracle’; and the contemporary crisis situation. In this essay I shall briefly discuss the period up until 1870. Trade in this region till this time could be said to have been dominated by Island Southeast Asia, so apart from general observations of Southeast Asian trade, I shall be concentrating on the archipelago.

Early economic activity

Economic activity in Southeast Asia up until the Second World War was largely characterised by subsistence modes of production, with rice overwhelmingly dominating the agricultural landscape. Even up to the 18th century all regions of Southeast Asia were still dominated with traditional agricultural patterns of existence, with a complete absence of modern industry.[3]

As a general rule, swidden agriculture was practised in the highland areas of mainland Southeast Asia and in the dryer regions of the eastern Indonesian archipelago.[4] Slash and burn agriculture encourages a semi-nomadic mode of existence, as the cleared forest area would retain its fertility for no more than a few years.[5]

In the more populous plains or valley regions wet rice production was practised.[6] In contrast to swidden, wet rice agriculture required a high degree of technological, social and political organisation. The elaborate irrigation schemes and hill terraces required a level of co-operation beyond the capacity of the single-family group, to include an entire clan or village or group of villages. Supplementing the basic diet of rice, peasants grew fruit and vegetables, and raised chickens, ducks, pigs, goats, and in some cases freshwater fish. To a larger extent, the traditional Southeast Asian village was economically self-sufficient.[7]

Beyond subsistence, agricultural surplus played an important part in the life of traditional Southeast Asia, as communal storage for lean years, as tribute to rulers and suzerains, and as goods to be used as exchange with the surpluses of neighbours. These modes of exchange are pre-capitalist in their nature, as the surpluses produced were often incidental, over and above that required for survival of the individual peasant family or village.

As villages became larger specialist artisans could be supported, often working as a sideline to their main agricultural activity. In some cases entire villages would be given over to one particular trade. Agricultural surpluses could be thus exchanged for commodities such as salt, pottery, paper, and cloth.[8]

The Trading States

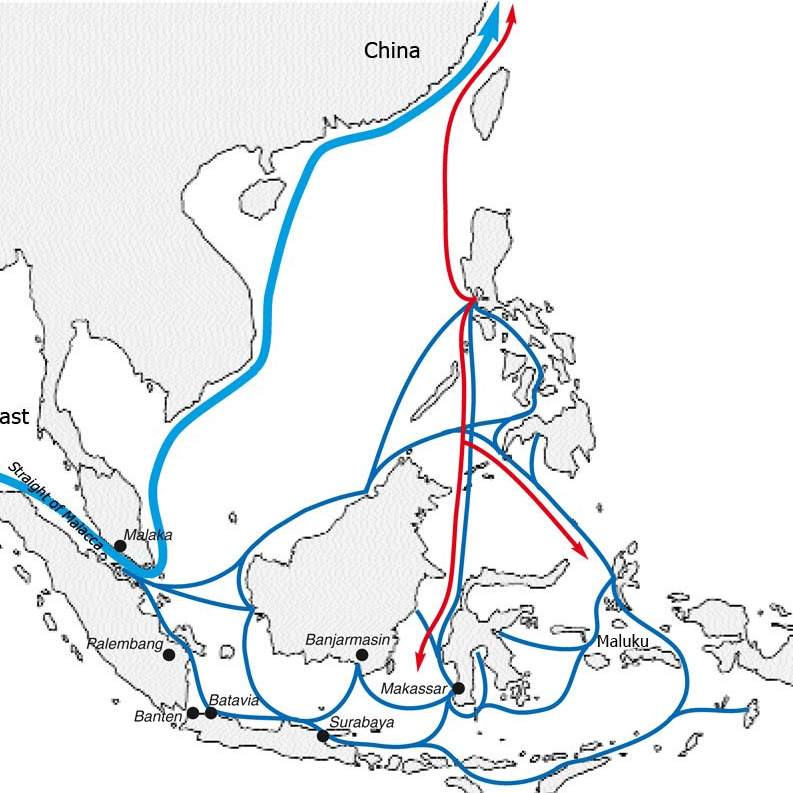

The appearance of Chinese ships is considered an index of the economic and political history of maritime Southeast Asia.[9] Beginning at around the 7th century the trading ‘state’ of Srivijaya began its emergence. It covered both sides of the strategic Straits of Malacca along the coasts of the Malayan Peninsula and the island of Sumatra.[10] Srivijaya’s role or activity could have been more that of a toll-keeper, rather than trader, controlling as it did the important trade between the Middle East, India and China through its control of the Straits. As a consequence of geography Srivijaya became a major Asian emporium of its time.[11] Indeed, Srivijaya was the forerunner of later maritime powers that gained their wealth through their control of the sea routes.[12]

The trading ports of Srivijaya started to decline in importance the 11th and 12th centuries, ultimately to fade away in the 14th century when another Straits empire emerged to take its place. The Sultanate of Malacca rose to prominence as a major trading entrepot in the 15th century. It is claimed that Malacca was one of the major world trading ports of its time and considered richer than London.[13] Unlike Srivijaya, Malacca was a kingdom professing and propagating Islam, and its influence was felt throughout island Southeast Asia reaching as far north as the modern Philippines.

Malacca was much more than a just a tollgate; it was an active trading city-state. Malacca’s influence extended throughout the region, it being the centre of a vast intra-island trading network into which the wealth of the region was directed and concentrated; Indian cloth, rice and teak ships from Burma, pepper and tin from Sumatra and the Malayan Peninsula, and nutmeg and cloves from the Moloccas.[14]

Whilst Srivijaya and Malacca waned as trading powers, their influence has carried on to the present day in the form of a trading language, Malay, that spread throughout the coastal regions of island Southeast Asia, and of course became the basis of the modern national languages of Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei and Singapore.[15] Malay constituted the commercial lingua franca of the archipelago, and thus, along with Islam, must be considered major factors that tended to unify the diverse cultures of the island worlds,[16] at least along the coasts.

Malacca’s power, both commercial and political, was soon weakened upon the arrival of the first Europeans, the Portuguese, who captured the town in 1511. Thus started a long period of decline for the sultanate.

European Influence

European expansion into Southeast Asia was slow and haphazard.[17] It was the lure of spices - in particular cloves, nutmeg and pepper - and the desire to cut out the middlemen of the Middle East, which first drew European privateers into the region. Thus the single most important factor bringing them to Southeast Asia was the prospect of becoming involved in an existing pattern of trade[18] rather than establishing new patterns.

The nature of European impact was highly varied throughout the region, and the force of this impact was very uneven.[19] In fact, it was centuries before the full force of colonialism touched the everyday life of the peasant, in particular in the inland areas. For some time Europeans were just another nationality entering the markets of the region.

However the Europeans came with perspectives of conquest and monopoly rather than a purely trade perspective, and were able to back this up with superior military technology and organisation whenever they lacked in business acumen or trade goods. Moreover, because of these perspectives, the European colonials unwittingly tended to destroy the objects of their conquest. The Portuguese take-over of Malacca signalled the beginning of a long period of decline for this city-state. The Portuguese fundamentally misunderstood the nature of the trade of which Malacca was the centre, seeking to impose monopoly domination over the spice trade. They succeeded merely in forcing many regional traders to other ports, in particular Johor. The Portuguese attempted to control a string of strategic ports stretching from Malacca to Maluku, rarely penetrating the interiors and never establishing plantations or industry.

The Portuguese were soon supplanted by the Dutch as the main European presence in the Island trade region. After the seizure of Ambon in the Moloccas in 1605 and Banda Island in 1623, the Dutch secured the trade monopoly of the Spice Islands. A policy of the ruthless exploitation by ‘divide and rule’ tactics was carried out. Indigenous inter-island trade, like that between Makassar, Aceh, Mataram and Banten, as well as overseas trade, was gradually paralysed.

To reinforce their spice monopoly in Molloccas, the Dutch undertook their notorious Hongi expeditions, burning down the clove gardens islanders in an effort to eliminate the overproduction which brought down the prices of cloves on the European markets.[20] For a period the Dutch succeeded in their aims to gain a monopoly over the Southeast Asian spice trade. In doing so they also began a long process of peasant impoverishment within the archipelago.[21]

The general European colonial pattern of divorcing producers from their traditional markets recurs throughout Southeast Asia. Without exception, colonial domination shamelessly subsumed the needs of the dominated towards the needs of the colonial power. Once powerful trading cultures within Island Southeast Asia in particular, with it’s strong regional networks, were gradually crushed under the weight of colonial influence, although local factors also came into play. The Mataram wars against the Islamic ports of the north coast of Java in the early years of the 1600’s also played a significant part in the decline of this trading culture, and ‘condemned the once-flourishing Javanese merchant class to centuries of obscurity in the backwaters of Javanese life.’[22]

The social impact of trade has indeed been profound for Southeast Asia, arguably more than in any other region on Earth. However, up until the late 1900’s, and perhaps even beyond in many cases, it needs to be remembered that the vast majority of people in the region remained virtually untouched by the influence of trade. For the most part, the influence of international trade and its attendant imperialism was limited to the coastal ports and adjoining regions. Peasant life in the main continued as it always had, oblivious and uncaring for the world outside the confines of the village.

Notes

[1] Stange, P (1995) Ancestral Voices in Southeast Asia, Murdoch University, Perth: 99

[2] Stange: 88

[3] Osborne, M (1990) Southeast Asia: an illustrated introductory history, 5th ed., Allen & Unwin, North Sydney: 60

[4] Burling, R (1965) ‘Hills and Plains’ in Hills, Farms and Padi Fields: Life in Mainland Southeast Asia, Prentice Hall, New Jersey: 4

[5] Osborne: 55

[6] Burling: 4

[7] Steinberg, D J (ed.) (1987) ‘Introduction’ from In Search of Southeast Asia: A Modern History (revised edition), Allen & Unwin, Sydney: 12

[8] Steinberg: 14

[9] Wolters, O W (1982) ‘Historical Patterns in Intra-Regional Relations’ from History, Culture and Region in Southeast Asian Perspective, Singapore: 23

[10] Osborne: 20

[11] The historical and archaeological record for Srivijaya is weak and partly speculative. This is my modest contribution to such speculation. :)

[12] Osborne: 84

[13] Steinberg: 57

[14] Steinberg: 57

[15] Albiet, most Singaporeans are unaware that their national language is Malay, and in the main display disdain for it.

[16] Language is not culture-neutral of course; words convey meanings beyond the purely lexical, containing assumptions about the nature of the world and of the worldview of the particular language user.

[17] Osborne: 76

[18] Osborne: 84

[19] Osborne: 62

[20] Indonesia 1995: An Official Handbook, quoted at http://www.indonesianet.com/hilight/hiancien.htm by IndonesiaNet Inc 1996

[21] Osborne: 85

[22] Steinberg: 84